By combining environmental sustainability with commercial sensibility, start-up Good and Fugly is reducing the amount…

Stale National Food Plan needs refreshing

Agriculture is inextricably linked to the cost of living. Households in NSW spent $11,363 on food in 2020/21, which made up 9.6 per cent of the total household spending budget, an increase from 8.7 per cent in 2015/16. Nonetheless, attention is only paid to food prices when one-off events cause individual items, such as lettuce, to reach eye-watering heights, before subsiding into the background of political consciousness.

This is in direct contrast to the cost of utilities, which accounted for only 3.1 per cent of household expenditure in 2020/21. However, it is the recent energy price increases which have led to acknowledging that a complete structural transformation of the sector is required, underlined by the $20 billion investment in transmission lines announced in the recent Federal Budget.

Our food and agriculture system, however, remains on the policy periphery, despite its share of household expenditure being over three times that of utilities. For example, the National Food Plan is almost a decade old and has only been gathering dust rather than guiding strategic interventions. There is no national climate change policy for agriculture. There is no sustainable funding source for biosecurity. There is no lead agency responsible for addressing problems in our food system. The list goes on.

As food is a necessity, its price and any associated increases have important implications for the welfare of society and the broader economy. Food affordability is a function of food prices and household incomes. Wage growth was 2.6 per cent over the year to June 2022, while food prices over the same period increased by 5.9 per cent (with a further increase to 9 per cent over the year to September). With food prices increasing at a faster rate than income, food is becoming more expensive and difficult for families � especially those experiencing disadvantage � to afford. The top cause of food insecurity in FoodBank�s 2022 Hunger Report was the rising cost of food and groceries.

There are also broader economic implications. As food is a necessity, it needs to be purchased regardless of income levels. Therefore, as food gets more expensive, it takes up a higher proportion of the household budget, leaving less money to spend on other more discretionary items and to save.

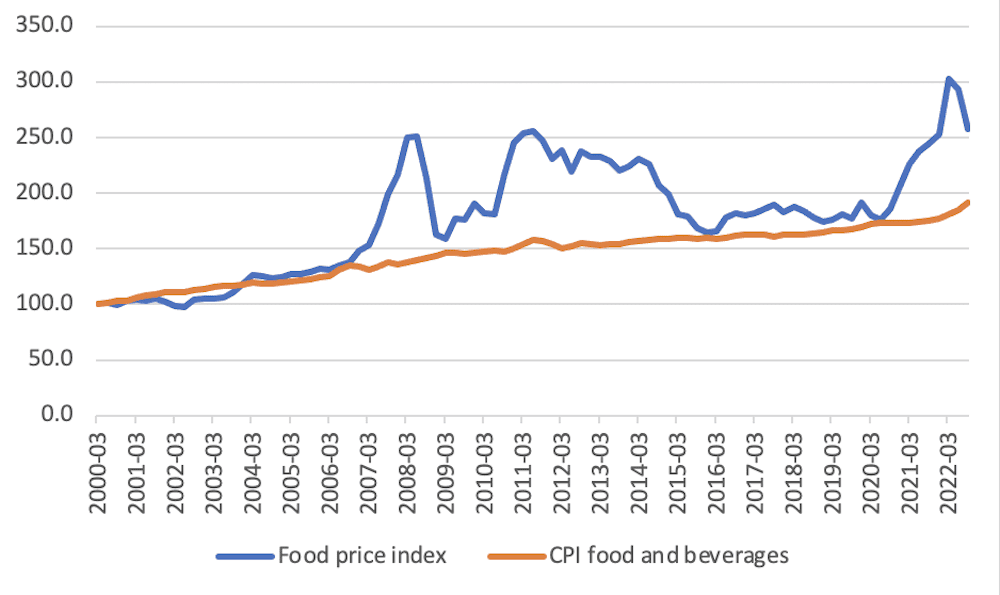

Food prices have not historically been a contentious issue in Australia, with an abundance of land leading to high per capita levels of food production, and deregulation resulting in both productivity gains and low prices from increased competition. Figure 1 compares the food and non-alcoholic beverage consumer price index (CPI) to the global Food Price Index compiled by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It shows how food prices in Australia were immune from spikes that occurred from 2008 to 2015, and even during the beginning of the pandemic. The uptick in 2021-22, however, indicates that the situation may be changing.

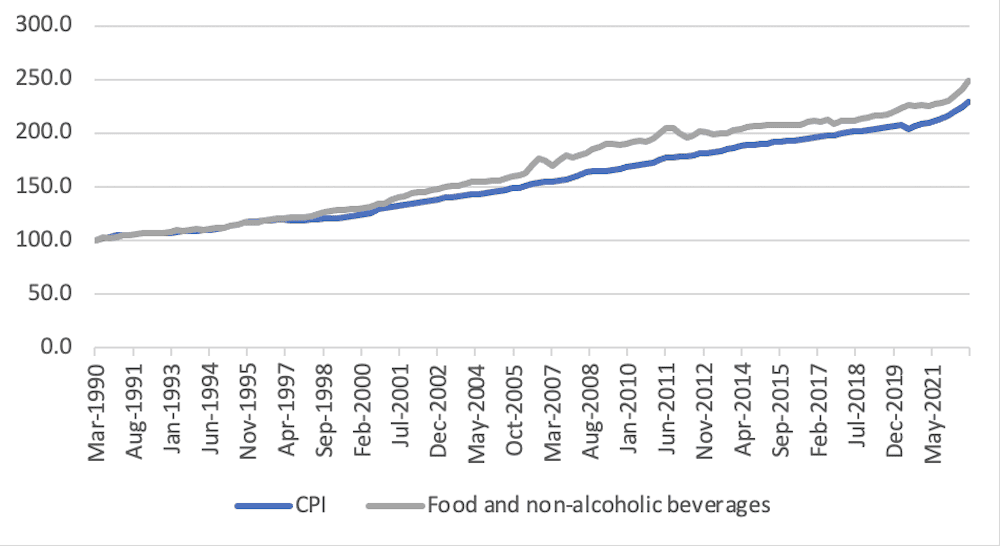

Data on a more localised level is also enlightening. Figure 2 shows how local prices for food and non-alcoholic beverages have decoupled from the CPI since 2000 and continues to be at a higher price level. Ideally, we would want the opposite to occur; a resilient food and agribusiness sector which provides affordable food to consumers regardless of external shocks.

To achieve this and build on the gains already made by the sector, Australia needs a renewed National Food Plan which is evidence-based, embedded in government activities, reported against, subject to monitoring and evaluation, and clearly articulates the importance of the agricultural industry as a foundation of food security in Australia � and globally.

Guidance from Canada and the UK

Canada and the UK are two countries that have already started on this important journey, and which Australia should look to for guidance.

The Food Policy for Canada has the following overarching goal: �all people in Canada are able to access a sufficient amount of safe, nutritious and culturally diverse food. Canada�s food system is resilient and innovative, sustains our environment and supports our economy.�

This statement recognises the two sides of food security: the first part addresses consumption while the second is concerned about production levels, including environmental services.

These are two fundamental elements of the policy which should be adopted by any Australian policy. The Canadian Food Policy Advisory Council (CFPAC) provides advice on the nature of food challenges and solutions to address them while also aiming to build trust among key food system stakeholders to support the ability to collaborate across sectors. Reporting on results is a crucial way to measure and track progress towards outcomes and support evidence-based decision making.

The six long-term outcomes being tracked by the CFPAC are: vibrant communities, increased connections within food systems, improved food-related health outcomes, strong indigenous food systems, sustainable food practices and inclusive economic growth. Only one of these outcomes, however, directly addresses the goal of a �resilient and innovative� production system.

As a further example of leadership in this field, the UK Government Food Strategy, released in June this year, more explicitly addresses supply issues which have implications for food production and, by extension, food security. For example, it includes a commitment of �390 million (A$695 million) to develop new farming systems through agtech and innovation, and working with the Migratory Advisory Commission to review occupation shortages in the agricultural sector.

While these two policies provide some guidance, experiences in the energy and waste sectors closer to home show the dangers of short-term planning of essential public services.

�Unfortunately, we�ve had very little action in the electricity system from the federal government in the last 10 years which means we�re not as set up as we could have been for a smoother transition.�

Amanda Mackenzie from the Climate Council

Australia has now run out of time to replace old, expensive and polluting coal-fired power plants, with the result being retail electricity prices expected to soar by up to 35 per cent as the system struggles with the energy transition and a global supply crisis.

The fragile domestic waste industry was exposed when China stopped accepting the world�s waste in 2017. This led to a complete breakdown of the system, with the double-edged sword of costs to councils and therefore ratepayers skyrocketing, and recyclable materials being sent to landfill.

These two crises, however, have led to meaningful action. The NSW Electricity Infrastructure Roadmap is expected to attract $32 billion of private investment into the energy sector while the National Partnerships on Recycling Infrastructure aims to fill critical infrastructure gaps in Australia�s waste management system with over $1 billion of investment. Food insecurity is increasing in Australia, and it is time to strategically invest to solve structural issues in the system rather than waiting for a crisis to occur to make significant change.

First steps to national food strategy

While meaningful action in the agricultural sector in respect of bolstering food security remains slow, there is some good news. On October 26, the Federal Minister for Agriculture referred the House Standing Committee on Agriculture to commence an inquiry into food security in Australia. Hopefully this is the first step towards the creation and implementation of a national food strategy.

There is also an inquiry happening into food production and supply by the NSW Legislative Assembly Committee on Environment and Planning. The final report was released on 1 November 2022 and the government response to this report is due on 1 May 2023. The overall findings of this inquiry were that:

- The approach to the food system is siloed and disjointed.

- Various government agencies are responsible for separate policies.

- There is no overarching government plan or strategy to address issues with food security and food supply.

- There is no lead agency that is responsible for addressing problems in our food system.

The overall recommendation to deal with these issues is that the NSW Government should develop a comprehensive Food System Plan for NSW, with clear objectives and measurable targets. It is also pleasing to see that similar to Canada�s Food Policy Advisory Council, it recommends the creation of a Food System and Security Council to implement the plan and act as a single coordinating body.

There is also the recognition of agriculture�s role in food security, with several specific recommendations targeting systemic supply issues including:

- The adoption of policies to limit the ability of major retailers to impose aesthetic standards for produce, leading to significant food waste.

- The creation of land use offices in food production regions to help businesses adapt to and benefit from the renewable energy transition.

- The requirement for consultation with experts and stakeholders from industry and regional communities to develop a long-term food workforce strategy.

- The requirement to set up a Help Harvest NSW network to help employers coordinate and promote work opportunities mapped to supply and demand cycles in specific regional areas.

While these are welcome initiatives, one noticeable gap is the need to support farmers adopting sustainable farming practices. The only action taken at this stage is on the demand side, through a sustainability labelling system for packaged food. Action already being taken by the NSW and Federal Governments in this space remains slow and disjointed.

More needs to be done, and quickly, to ensure that sustainability is recognised as a core requirement for the food system which will lead to increased investment and coordinated action.

A National Food Plan will ensure that the difficulties faced by Australia�s primary producers and agribusinesses nationally are alleviated. The reality is that agriculture is the very foundation of food security, with important contributions to climate change, biosecurity, health and environmental sustainability. Indeed, a coordinated and considered National Food Plan will ensure the sustainable delivery of safe, healthy, affordable food � regardless of where people live or how much they earn.

If this story on the National Food Plan was of interest to you, you might like to read our feature on growing native foods with First Nations knowledge.