The United Nations declared 2012 the International Year of Co-operatives and Australia marked it as…

Of mice and men – the plague erupts

North West farmer James Nalder awoke at his Coonamble property each morning during the mouse plague to the stench of rotting flesh. A bumper grains harvest and near-perfect summer season has provided the ideal breeding conditions for mice. James says they’ve been relentless.

“People are waking up with them on their face, or in their boots when they pull them on in the morning. They’ve chewed through cables in vehicles, they’re dying in our air conditioners, and some people wake to find hundreds in their pool, every single day.

“They’re destroying haystacks before our very eyes. There are haystacks right around the district which have been turned to chaff in a matter of weeks.”

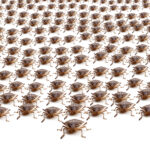

Scenes where literally tens of thousands of mice can be found scrambling out of sheds, haystacks, silo bags and cropping paddocks have defined the past few months for farmers across the state’s North West region.

Photo by James Nalder

The plague problem extends from Queensland’s Darling Downs region in southern Queensland into NSW, with major problems around Moree, Walgett, Coonamble, Warren, Trangie, Gilgandra and Dubbo.

While authorities can’t put any kind of official number on it, farmers throughout the region are calling it the worst mouse plague in a generation – and it’s wreaking untold amounts of damage to grain and fodder supplies, in particular.

New and mature crops have been in the firing line, with significant damage to sorghum crops grown over the summer, and fear for what will happen to winter crops currently being planted.

NSW Farmers has lobbied the State Government to provide farmers an environment where they can take actions to combat mouse populations.

The Association has called on the Government to support and fast track applications with the APVMA for emergency use permits of rodent baits, for example to allow baiting with zinc phosphide on bare or fallow paddocks to assist suppress populations ahead of winter crop sowing.

The Association also called on the Government to provide a grants program with meaningful subsidies and rebates for baiting, accompanied by an extension program rolled out by Local Land Services to ensure farmers are aware of best-practice control techniques.

NSW Farmers says government agencies should assist and streamline approvals for industry to establish treatment stations so farmers can have their own grain professionally treated with zinc phosphide – currently the only effective mouse bait poison for use in broadacre settings. They say this would reduce a lot of the biosecurity risks posed by the use of introduced grain, and ease pressure on demand and cost for commercially treated poisoned grain.

Winter cropping nightmare

There are now big concerns about how to protect winter crops such as wheat, barley and canola, as it’s unclear how long it will be before the booming mouse population crashes.

CSIRO health and biosecurity research officer Steve Henry has been working with the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) to understand mouse behaviour and develop management options in zero and no-till cropping systems, which he said provide ‘stellar’ conditions for breeding and feeding mice.

“There’s zero disturbance and lots of shelter, lots of food. We are trying to understand ways to create an environment that’s unfriendly to mice in our cropping regions.”

Steve says the research has found farmers are leaving up to one tonne per hectare of residual grain – or mouse food – on the ground during harvest.

“Every farmer says their headers are set up properly, but we are finding in actual fact there is so much grain being left behind.

“Farmers need to focus on correct planting and harvesting machinery set-up, which limits feed for mice and maximises the opportunities for mice to take the baits instead.”

He said grain treated with zinc phosphide poison was currently the only form of control available in broadacre systems, and he urged farmers to closely comply with regulations surrounding its use as any deviation could result in the product being removed from the market.

Steve said it was difficult to predict when this outbreak would end. On one hand, conditions have been so favourable there is a very real chance mice will continue to breed all autumn, and cause major problems in winter crops.

However, there’s also a lot of evidence from previous mouse plagues that mice eventually start to eat each other, which triggers a population crash, and they disappear literally overnight.

NSW Farmers Agricultural Science Committee Chair Alan Brown said farmers were working hard to try and break the breeding cycle with this only known treatment currently on the market.

He said they are hopeful the Government will enact ‘emergency-use permits’ so farmers can treat their own grain with zinc phosphide poison, which would ease pressure on supply and demand for the bait and also help farmers get access to bait sooner.

“A female mouse can mature by six weeks of age and breed every three weeks, meaning the potential offspring for a pair of mice could be as high as 500 a year,” Alan explained.

“The most effective treatment so far has been the zinc phosphide treated-grain product, which – when used at the recommended rate – could kill up to three mice per square metre.

“An emergency permit system for this mouse plague would help dramatically cut the cost of treating affected areas, which are quickly rolling into the tens of thousands of dollars for many broadacre farmers, in addition to the unknown cost of damage which is also now extremely significant.”

Monitoring at Gilgandra

Gilgandra farmer Max Zell has been poisoning and monitoring mice around his sheds since mid-January.

He baits daily and tallies the fatalities each morning. Over a six-week period alone Max says he picked up more than 22,000 dead mice in and around his workshop and machinery sheds. Numbers peaked in mid-March, when he collected 4,000 dead mice in three days.

Max has been baiting using zinc phosphide, which he’s been hiding under pallets in his sheds to avoid poisoning native birds.

“They came in waves. We’d have a few quiet weeks and then they’d swamp us again,” Max said.“We are filling large 10-litre paint tins with dead mice, it’s hard to believe.

“It’s certainly as big as the enormous plague that swept through this area in the early 1990s. That was huge and did a lot of damage, and what we’re experiencing now is definitely equivalent.”

Max said the waves of mice have done immense damage to silo bags in the region and farmers were working day and night to try and offload grain before it was ruined, but it was a major logistical challenge given the record tonnages harvested at the end of last year and the large amounts of grain still not moved out of the area.

He says despite the huge numbers he’s still killing each night, he believes he’s broken the back of the breeding cycle, with the population definitely in decline.

“Baiting is helping to break the cycle – had we not started baiting we could easily have had 80,000-100,000 mice over-running our sheds. I think we’ve averted a major crisis.

“But I am still seeing waves of mice running out of grain bins and all over the road at night, so I’m not sure what it will take for it to all be over.”

5 quick tips for mouse control

• Apply broad scale zinc phosphide bait according to the label, at the prescribed rate of 1kg/ha.

• Apply bait at seeding or within 24 hours while seed is still covered by soil, increasing the likelihood of mice taking the bait prior to finding the seed. Rebait through the season as needed.

• Timing is critical. Delays of four or five days in baiting after seeding can give mice time to find crop seed. High populations can cause up to 5 per cent damage each night.

• Monitor paddocks regularly and update local data using the MouseAlert website www.feralscan.org.au/mousealert.

• Minimise sources of food and shelter after harvest and prior to sowing. Control weeds and volunteer crops along fence lines, and clean up residual grain by grazing or rolling stubbles.

If you want to read more about the mouse plague, see our story on bait rebates.