NSW Farmers is inviting all farmers hit by the 2019/2020 bushfires to fill in a…

Rewarding farmers for biodiversity initiatives

There�s been a lot of talk in the media, from various government spokespeople, and on tractors and utes around the country, about how farmers might be able earn additional income from planting trees both for biodiversity outcomes as well as carbon credits.

While it may be difficult to see the forest for those trees, one thing is crystal clear: Minister for Agriculture David Littleproud is on a mission to reward Australian farmers for their agricultural stewardship of the land with a world-first scheme that measures and rewards biodiversity improvements alongside carbon abatement.�

Recognising that agricultural land managers are responsible for managing 58 per cent of the Australian landmass, the federal government has budgeted $66.1 million for its Agriculture Biodiversity Stewardship Package, which it is developing in partnership with the Australian National University (ANU), the National Farmers� Federation (NFF) and Natural Resource Management (NRM) organisations to trial pilot projects, develop market arrangements, and kick start private investment in farm biodiversity.

It�s a tightrope act to create an environment policy that�s appealing and accessible to farmers while not aggravating Coalition MPs that have generally been opposed to emissions-reduction initiatives. However, the Minister believes that farmers have already done the heavy lifting because they know their profit and loss is tied to the health of their land.

�It�s not about locking up productive land but about rewarding farmers for the management and rejuvenation of unproductive land�

Minister for Agriculture David Littleproud

He believes this is an opportunity for farmers to make additional money that could be paid by big corporations, which are increasingly focused not only on reducing their carbon emissions but also on augmenting their social license through good news stories about investment in biodiversity and natural capital. To that end, the Minister has been in discussions with the Business Council of Australia about the viability of creating a biodiversity market similar to the carbon�market.

His Agriculture Biodiversity Stewardship legislation was tabled in parliament in February. It�s been a very tight turnaround in this election year and there are some concerns that mistakes will be made, however there is clearly a lot of momentum to make things happen.

�It�s really important for farmers to look at the legislative framework being constructed by the Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment (DAWE),� says Warwick Ragg, General Manager Natural Resource Management at the NFF and the key NFF negotiator on this legislation.

�Minister Littleproud is driving this initiative and there are some exciting opportunities on the horizon. Everybody involved in agriculture should understand the issues and start thinking about getting engaged.

�At the same time, it�s worth noting what the Agricultural Biodiversity Stewardship Package is and what it is not. The program is completely voluntary, not compulsory, and it�s nothing to be scared about. It�s not an additional compliance program and farmers will not have to unwillingly expose their process to the world.�

Warwick Ragg, General Manager Natural Resource Management at the NFF and the key NFF negotiator on this legislation.�

�The government is doing good work here. It�s not perfect, but things are moving in the right direction. It has arranged for consultants to go out and talk to the community, identify the problems, and test potential solutions with various trials. Obviously, some things get lost in the bureaucratic process, but the government is at least being transparent about how it�s going about fostering biodiversity.�

In their approach to the legislation, the NFF is taking a big-picture view to seek to ensure that Australian agriculture on a national level is verifiably sustainable both to minimise lending restrictions from financial institutions and to minimise export risks if Australian farmers have not complied with increasingly stringent international market requirements for clean, green products.

�In five years, these sorts of agricultural environmental standards are likely to be de rigueur,� says Ragg. �This is a rapidly changing landscape and, although this may be difficult to process, it�s worth being ahead of the curve.�

The stewardship package in a nutshell

The package, which is a multi-stage process being developed by experts from the College of Law and Fenner School of Environment and Society at ANU, is complex with lots of moving parts. To get an understanding of the current state of play, here is a snapshot of each element.

There are two rounds of Carbon + Biodiversity Pilots in six different National Resource Management (NRM) regions around the country. For NSW, Round One took place in the Central West. Round Two is currently underway in the Riverina.

This world-first program offers farmers two revenue streams: biodiversity payments up front and the opportunity to earn income down the track by selling Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs).

Essentially, farmers offer to deliver long-term biodiversity improvements through plantings (for which they are paid in two instalments) in conjunction with specific ERF environmental plantings of native trees and shrubs on land that has been clear of forest for at least five years in order to store carbon (and generate ACCUs). Farmers must maintain both planting projects for 25 years.

�This is important stuff,� says Ragg, �because it�s essential to understand the challenges of measuring biodiversity on its own as well as its carbon abatement potential. The ANU team has been developing the specific biodiversity metrics using improved habitat as a surrogate for environmental outcomes.�

Enhancing Remnant Vegetation Pilot was run in the same six NRM regions as Round One of the C+B pilot (in the Central West of NSW) with the goal of improving existing native vegetation on farms and testing the locally adapted biodiversity protocols developed by ANU.

Farmers enter contractual agreements with the Australian Government and receive regular payments to manage and enhance remnant native vegetation by installing fencing, weeding, pest control and replanting.

�The goal is to develop consistency on a national level as the current incentives differ across the states,� says ANU environmental law and policy expert, Professor Andrew Macintosh, who is one of the scheme�s architects.

The voluntary Australian Farm Biodiversity Certification Scheme Trial (part of the Carbon + Biodiversity Pilot) to showcase farmers� best practice natural resource management to sustain, build, and report on-farm biodiversity and enable consumers

to identify Australian produce from farms that sustain biodiversity. This certification could help increase farm profitability by supporting access to markets, creating price premiums, and improving land management practices.

The Carbon + Biodiversity component is the first time farmers will benefit from biodiversity initiatives and carbon abatement on the same land.�

�The Certification Scheme aims to provide farmers with tools to prove sustainability across five parameters: carbon sequestration, biodiversity, tree and land cover, and drought resilience,� according to Professor Macintosh. The National Stewardship Trading Platform (NSTP) is a single platform (https://agsteward.com.au) to help farmers participate in emerging environmental markets by:

� Providing planning tools to evaluate biodiversity and carbon projects

� Providing easy-to-use portals to apply to the pilot programs; and connecting them with potential buyers of biodiversity and carbon services.

�We�ve got to make this process easier for farmers,� says Macintosh. �The online marketplace is designed to function like a sort of eBay where buyers and sellers can meet. Ideally, the marketplace will help kick-start private sector biodiversity markets as well.�

Essentially, the marketplace will be a way to find project partners with confidence. It will help farmers monetise their biodiversity and carbon services by connecting them directly with private buyers and it will help private buyers find potential on-farm biodiversity and carbon projects that could be purchased or co-funded. Both parties can search the marketplace or create their own project listings for environmental services they�re looking to buy or sell.

Initially, the marketplace will list biodiversity-enhanced carbon credits but eventually the goal is to also create straight biodiversity credits once a tradable biodiversity unit has been established. Negotiations between farmers and buyers will occur privately, independent of the NSTP.

Farming perspectives

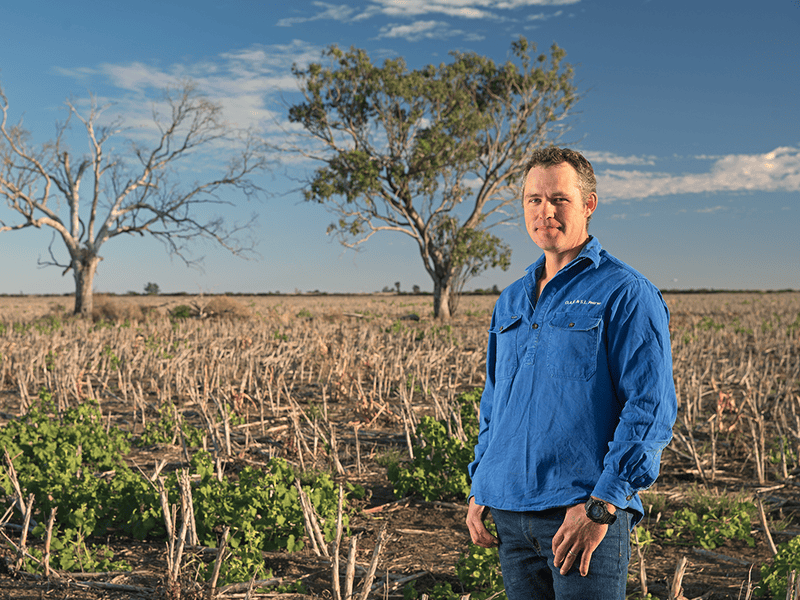

Oscar Pearse is a mixed cropping farmer from Moree and a former agricultural policy consultant with the NFF and other farming organisations. He says the Carbon + Biodiversity component of the Stewardship Package is a step in the right direction because this is the first time that farmers will be able to benefit from both biodiversity initiatives and carbon abatement on the same land.

�In the past, we effectively had to give away the hay when we sold the wheat. Farmers could essentially only choose between being paid for biodiversity outcomes or carbon, but never both,� he explains. �However, despite this positive precedent, farmers who are already good land managers will still struggle to benefit from the Stewardship Package because everything that�s been done in the past is not credited. This sends the wrong signal because it rewards the worst farm managers.�

NFF�s Warwick Ragg offers some context. �The carbon market was constructed on the principle of doing something additional to standard practice. However, this shouldn�t mean that every natural capital indicator, in this case biodiversity, must also be additional. Past quality management practices should legitimately have a value and be recognised.

�Of course, biodiversity must be identifiable and measurable. However, the government could focus on reimbursing new biodiversity plantings and let the markets decide on the value of existing biodiversity projects that have taken land out of production, if they so choose.�

Warwick Ragg, General Manager Natural Resource Management at the NFF and the key NFF negotiator on this legislation.�

�Different biodiversity buyers, such as banks, corporations, developers and philanthropic organisations, have varying needs/goals and different biodiversity projects could be valued accordingly. To that effect, the NFF is lobbying the government to ensure the legislation does not require additional or only �new� biodiversity as this could be determined by the market.�

Pearse has several other concerns with the current state of affairs. Firstly, he says, �Farmers, not the carbon aggregators, carry all the risks involved. They still have to comply with the make-good clause in most ERF contracts if trees they�ve planted don�t survive because of bushfires, drought or some other reason.

He also believes that the government has missed a valuable opportunity to facilitate the potential and benefits of carbon stacking, whereby multiple emissions reduction projects, such as plantings for biodiversity and carbon abatement, soil carbon sequestration, and methane reduction, are undertaken on the same property with a single, aggregated offsets report incorporating all the individual components.

Tools to help farmers in this new world

While the National Stewardship Trading Platform provides on-line planning tools to evaluate biodiversity and carbon projects, NFF�s Warwick Ragg believes many farmers will need a range of trusted sources to navigate this new commodity market.

�Farmers need to be able to cost effectively establish baseline measurements and have access to an array of decision support tools to make informed choices about their best options to reduce emissions and make money in the process. Carbon brokers do not necessarily operate in the best interest of farmers,� says Ragg.

�The NFF is working on a few things to move this along. We�re talking to Agricultural Innovation Australia about an investment proposal to resource farmers with decision support tools and we�re talking to various levels of government about the best ways to develop trusted advisors. Independent sources of truth and/or advisors for these �new commodities� will be critical to gaining farmer confidence.�

One new player in this space is the recently launched Regen Farmers Mutual created by a group of farmers, conservationists and land carers who have designed a farmer-owned brokerage to help farmers cost-effectively access environmental markets. Each member has one vote so that smaller farms are as powerful as large farms while all members benefit from the collective power of the mutual group.�

The brainchild of Andrew Ward, a cotton-grower�s son from Moree, Regen Farmers Mutual started in the cooperative farming community with farmers receiving fee support from the Co-operative Farming Program to attend co-design sessions. It has since spread to Land Care groups and regional farming groups, such as wine growers in the Riverland, and Ward is confident that the model will also appeal to mainstream farmers.

Their first product, the Environmental Farm Assessment, which costs $1,000 for members, will enable farmers to create their farm�s digital twin to get an indicative assessment of the value of all their environmental assets.

�We aim to align our on-farm environmental services (such as carbon abatement, biodiversity outcomes, species, habitat or water restoration) with what each buyer wants and, when they buy, 80 per cent of the revenue will go to the farmer, 10 per cent to the relevant farm group and just 10 per cent will go to Regen Farmers Mutual to cover overheads. This will ensure that farmers get a fair deal for their land stewardship,� says Ward.

�One of our key insights in co-designing the mutual with farmers was that they most wanted to hear from other farmers and least wanted to hear from the government and corporate brokers,� says Ward. �Eventually, every farmer will need to reduce their emissions. Our goal is for farmers to work together to design environmental solutions and not get shafted in the process.

�There�s still a real mismatch between the level of carbon abatement that can be produced on a typical family farm and the market appetite for large-scale offsets,� explains Ward.

�Regen Farmers Mutual can partner with existing farmer and member organisations to supply a range of offsets at scale, which is much more extensive than what individual farms can do. In this way, the Mutual can maximise returns for its farmer members while leveraging the networks they belong to. This is where things get really exciting.�

If you enjoyed this story on the importance of biodiversity initiatives, you might like our feature on the pathway to a $30 billion ag sector by 2030.