Australia�s city-dwellers are having a change of heart. Due to the pandemic, house prices are…

A farmer’s choice: to GM or not to GM?

Choice, competitiveness and confidence have been identified as the primary benefits from the NSW Government�s decision to allow the commercial production of genetically modified (GM) food crops.

The moratorium, specific to GM canola when it was first imposed in 2003, has been rewritten and extended several times during the past 18 years. In March, NSW Agriculture Minister Adam Marshall announced it would be allowed to lapse on 1 July.

The move gives farmers a greater choice of which crops to grow and provides certainty for researchers and seed companies that the path to market will be smoother for new

GM varieties.

NSW Farmers Association Ag Science Committee Chair Alan Brown says it will allow the state�s growers to remain competitive with their overseas counterparts.

�The world has moved on, as far as GM goes in food crops. We�ve had GM crops in cotton and canola for some while now. In the medium term, if there are developments in food crops, we will be able to access them. We won�t be left behind, which I think is important.�

Alan Brown, NSW Farmers’ Association Ag Science Committee Chair

Until now the only GM crops grown in NSW have been cotton and �blue� carnations (since 1996), canola (since 2008) and safflower (since 2019).

Alan, who is also NSW Farmers� Wagga Wagga and District branch Chair, says he�s hopeful plant breeders will now be able to use GM techniques to boost crop performance by incorporating features such as drought tolerance, improved nutrition profiles and better yields.

�But the key outcome for NSW Farmers is there will be safeguards put in place, so that those who don�t wish to have the GM technology on their properties will be able to continue without it,� Alan says.

�If there�s a trade advantage in not having GM, people will still be able to access that.�

New methods, new markets

One example is the Riverina Oils and BioEnergy crushing and refining plant at Wagga Wagga, which supplies certified non-GM canola oil to food manufacturers and food service customers.

Thomas Elder Markets analyst Andrew Whitelaw says the history of GM crops in Australia shows there have been few problems caused by cross contamination or market access issues, thanks to our advanced storage and handling systems.

�We have a big market at the moment for non-GM canola into Europe. The reality is that we�ve been doing that for a long time and the majority of that canola comes from Western Australia, where the bulk of our GM canola is grown. So, if it�s worked so far, then I don�t really see why it wouldn�t continue working.�

Andrew Whitelaw, Thomas Elder Markets analyst

Australian Oilseeds Federation Executive Officer Nick Goddard says grain growers have mostly used GM canola in a tactical way, to manage weedy paddocks.

�It�s quite different to cotton, where it was just broadly adopted across the board because it provided immediate benefits in terms of reduced chemical applications and reduced labour,� Nick says.

�The real opportunity for GM and all new breeding technologies is in being able to create and access new markets for renewable plant-based products.�

Improved genetics means a faster turnaround

CSIRO Agriculture and Food Chief Research Scientist Surinder Singh says scientists have always taken a long-term perspective in their crop research, regardless of government policy.

Creating a new variety using conventional breeding techniques can take plant breeders 10 to 20 years. Using GM techniques significantly speeds up the process.

And while the NSW moratorium didn�t stop that research, Surinder is optimistic that lifting the ban will accelerate the process of delivering improved genetics to farmers.

The CSIRO has developed two GM oilseed crops, and both were approved in 2018 for cultivation and use in stockfeed and human food.

Nuseed markets the GM canola, which is the world�s first plant-based source of long-chain omega-3 oils traditionally found in fish. The oil is used as an ingredient in fish feed for farmed salmon (Aquaterra) and for human consumption (Nutriterra). Nuseed estimates one hectare of the canola can produce as much omega-3 oil as 10 tonnes of fish.

Go Resources holds the licence to commercialise a stable super high-oleic acid safflower which produces oil suitable for industrial and edible uses. Now available at Woolworths supermarkets under the Heart Smart label, it claims to be the only cooking oil with a 4.5 health star rating.

The process of developing and bringing the two crops to market took about 15 years.

�We did the research in about four or five years, but then the regulatory approvals and all that take a long, long time,� Surinder says.

The way GM technology is used has evolved in the past decade with the advent of genome editing which targets specific sections of DNA and allows them to be permanently modified.

In the case of a wheat variety susceptible to rust infection, it could be tweaked or the gene removed to make it resistant to the pathogen, without inserting any new DNA from another source.

Surinder says current research to make crops more resilient to climate change and the challenges of drought, temperature, heat stress and salinity, is �fairly advanced�.

�They could be released in the next five to 10 years, but that depends on how readily the investment is there to actually get these crops through the regulatory approvals, which is a very expensive procedure,� he says.

A debate spanning decades

Debate continues over the role of genetic modification in food almost 30 years after the first crops of GM tomatoes, potatoes and corn were grown in the United States.

Released in 1994, the Flavr Savr tomatoes were engineered to have a longer shelf life and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) incorporated into potatoes and corn gave those plants protection against insect pests.

Their commercial success was mixed � Monsanto shelved the tomatoes � but they paved the way for the development of multiple varieties of food and fibre crops, including Australia�s first GM crop, Bt cotton.

Developed by the CSIRO in partnership with Monsanto, Bt cotton is resistant to a major pest, the heliothis grub, also known as cotton bollworm. Launched in 1996 under the trade name Ingard, it has since been superseded by newer varieties offering herbicide tolerance as well as resistance to insects.

Adoption in NSW, where most of Australia�s cotton is produced, was relatively swift. By 2012, almost all cotton was GM and the use of insecticides had decreased 97 per cent.

According to Cotton Australia, the flow on benefits include lower labour and fuel usage � crops now receive up to three pest sprays per season instead of 10-14 � improved soil quality, reduced production costs, increased yield and reduced risks.

Politics and well-fed Westerners

Much of the criticism of GM is tied to politics and ideology. Concerns include the potential harm to human health and damage to the environment, negative impacts on traditional farming practices, excessive corporate dominance, and the �unnaturalness� of the technology.

Internationally-renowned microbiologist Jennifer Thomson has written four books on the subject of GM crops since she began working in the field in South Africa in 1978. Her latest book, GM Crops and the Global Divide, was published in January.

In the book, Jennifer refers to the prejudices of �well-fed Westerners� and attributes part of the rise of antagonism to GM crops, especially in Europe, to government mishandling of two disasters in the United Kingdom in the 1980s and 1990s: the mad cow disease outbreaks, and HIV- and hepatitis-tainted blood transfusions.

The hostility was further fanned in 1999 by a media storm and tabloid newspaper headlines which referred to GM as �Frankenstein food�.

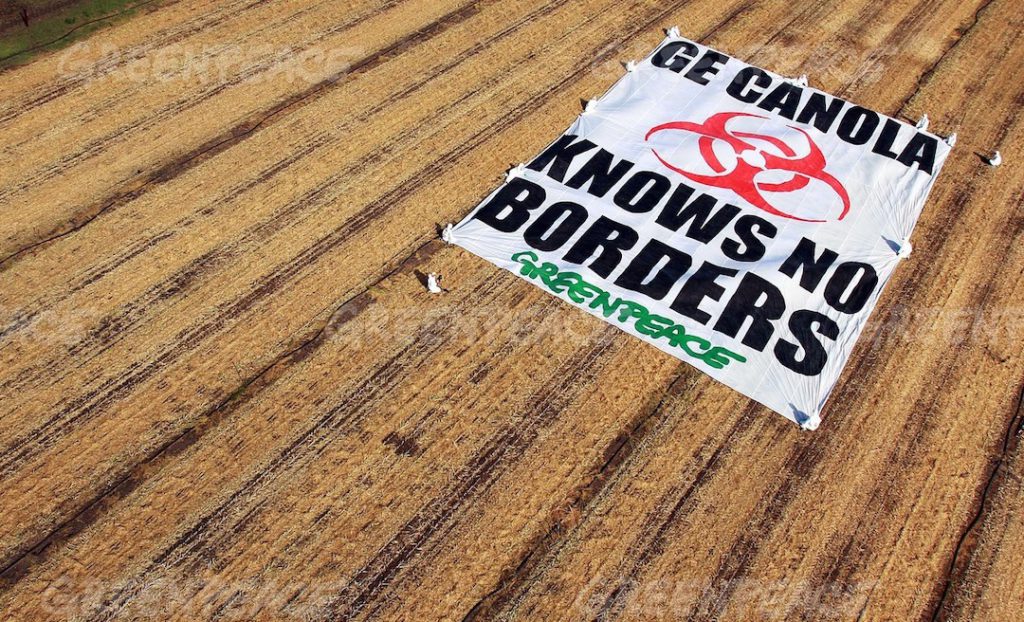

Greenpeace dumped four tonnes of GM soybeans outside the official residence of then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair at 10 Downing Street and its activists took to vandalising GM crops across the globe, including a trial crop of wheat at a CSIRO facility in Canberra in 2011.

The Greenpeace Australia website, which says �Climate change is the defining issue of our generation�, shows its priorities have changed in the past decade. The most recent references to GM crops are from 2012, and a Greenpeace spokesperson declined to comment for this story.

Jennifer says it�s essential for Australian scientists to do more to communicate the benefits of their work for farmers and consumers.

�Scientists need to get into the limelight, and explain what disinformation is, what is misinformation, and what is true,� she says.

�With global warming and climate change, you�ve got to do more with less. We�re going to have less suitable land to produce crops.�

Improving the bottom line

A 2011 UK study found the average cost of discovering, developing and authorising the biotechnology trait of a new plant between 2008 and 2012 was $US136 million.

That sounds like a lot of money, but it�s dwarfed by the potential economic benefits

of adopting GM crops.

In a statement, NSW Agriculture Minister Adam Marshall says adoption of GM technology is forecast to deliver up to $4.8 billion in total gross benefits in the next decade.

It could save farmers up to 35 per cent of their overheads and boost production by almost 10 per cent.

�The potential agronomic and health benefits of future GM crops include everything from drought and disease resistance to more efficient uptake of soil nutrients, increased yield and better weed control,� he says.

�This is also great news for consumers as by lifting the ban we are empowering companies to invest in GM technology that has the potential to remove allergens such as gluten, improve taste and deliver enhanced nutrition.�

Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia�s Kangaroo Island are the only Australian jurisdictions to retain GM-free status.

Keeping Australia safe

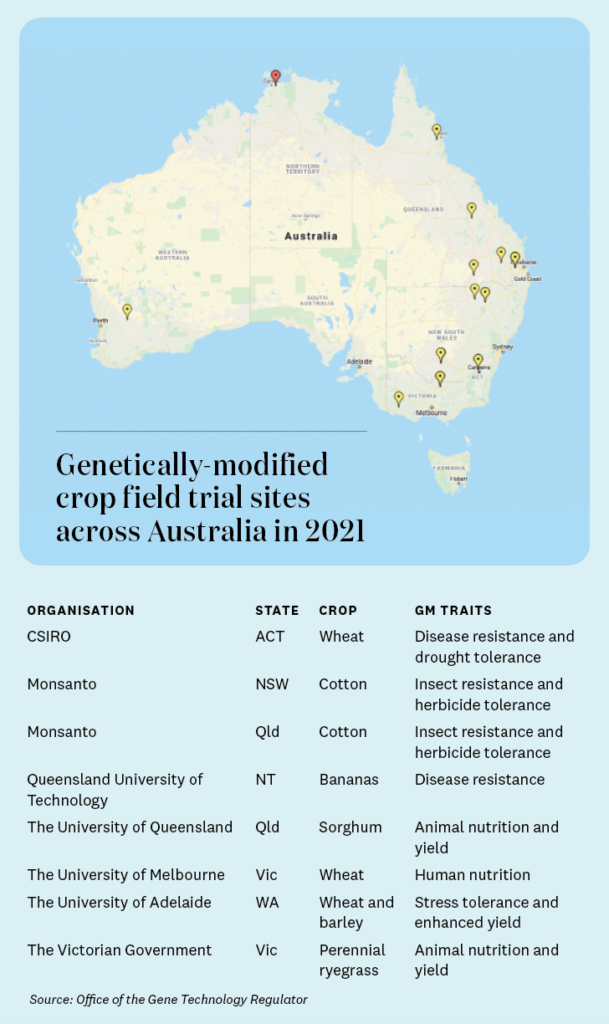

The Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR) was established in 2001 to license field trials and approve the commercial release of GM organisms that posed no unmanageable risks to humans or the environment.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) regulates the sale and use of food from GM products. It has so far approved eight GM food crops: soybean, potato, wheat, rice, canola, sugarbeet, safflower and corn.

Earlier this year, FSANZ approved the use of GM soy leghemoglobin, a protein used by Impossible Foods to manufacture its meat-free burgers and sausages.

The agriculture industry is embracing innovation in a big way, with vertical farming a key area of growth. Find out more about it here.