One of the major changes we will see over the next 10 years will be…

R&D and the bright future of agriculture

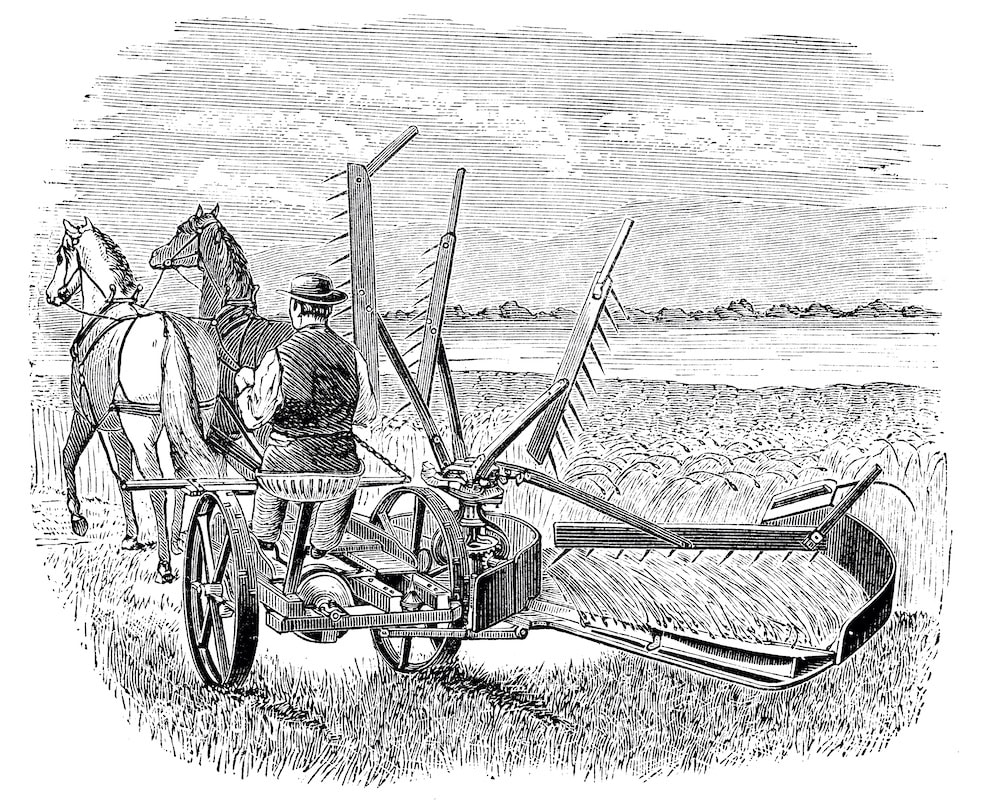

R&D in agriculture has come a long way since the former NSW Department of Agriculture was set up in 1890. Experimental farms were established across the state and wheat research began in 1893, with trials of more than 200 varieties at Wagga Wagga by plant pathologist Nathan Cobb.

Celebrated plant breeder William Farrer, who was appointed the department’s Wheat Experimentalist in 1898, went on to release numerous Australian-bred wheat varieties. Uptake of the first – the rust-proof and drought-resistant Federation variety – was swift. It helped quadruple the area of wheat grown in NSW and held the title of the most widely planted wheat in the country from 1910 to 1925.

Tools and techniques developed since then revolutionised agriculture, and the productivity of our farms steadily increased until the late 1990s – when it stalled. This prompted much discussion about how to reinvigorate productivity growth once the Millennium drought had broken.

Looking ahead to 2030

In 2017 the National Farmers’ Federation announced an industry-wide target to grow the value of Australian agricultural production to $100 billion by 2030.

The NSW Farmers Association last year released its own blueprint for reaching $30 billion in output by 2030, and Meat & Livestock Australia launched its CN30 Roadmap for achieving carbon neutrality in the red meat industry by 2030.

The NSW Government is backing those goals, so far committing almost $100 million towards the Department of Primary Industries (DPI) world-class Food and Fibre Program.

NSW DPI Director General Scott Hansen says the program recognises that incremental change will not be enough to achieve the ambitious 2030 targets.

Scott says achieving that kind of growth will require step changes – significant shifts – in production systems, as well as developing new products and opening new markets.

“R&D is going to be a critical component to this,” he says. “It’s not going to be enough to continue to make small gains with current technology. We’re going to need some big step changes to bring our industries forward in leaps and bounds.”

NSW Farmers CEO Pete Arkle agrees, saying the ambitious 30 by 30 target will not be reached without leading edge R&D and extension.

“We are fortunate to have the DPI in NSW, with over 600 DPI scientist and technical staff, many who are ranked in the top 1 per cent of world research in ag science,” Pete says.

“If we are to reach 30 by 30, it is critical that strong support is maintained for DPI’s R&D. We also need to ensure our extension systems are effectively cascading new innovations onto farm.

“NSW Farmers still has policy on its books from 1995 that we conduct a militant campaign to protest any forecast cuts to NSW Agriculture – let’s hope it doesn’t come to that.”

Pete says that the Association has been supporting members to embrace agtech innovation in a number of ways.

“So far in 2021, 250 farmers have attended a NSW-Farmers run drone course,” he says.

“Pleasingly the NSW Government also supported NSW Farmers’ Agtech Rebate proposal, with $48 million being committed in the recent State Budget and we continue to advocate for improved digital connectivity through both State and Federal investment.”

The DPI’s Food and Fibre Program includes upgrades for research infrastructure that has, in some cases, been in use for more than 130 years.

It will fund new glasshouses, exotic disease diagnostic instruments, on-farm sensor and data technology networks across DPI institutes, and new facilities for aquaculture and fish breeding research, and plant pathology laboratories.

The aim is to deliver a new generation of scientific breakthroughs in drought tolerant crop varieties, data-driven on-farm decision making, fast-tracked genetic improvements in beef and lambs, and new biological methods of pest control.

Scott is especially excited by the rollout of controlled environment facilities, including glasshouses and greenhouses, which will help accelerate research into horticulture, grain and pasture crops.

Already an experimental line of desi chickpeas, CBA2061, which has novel herbicide tolerance, has made it into the National Variety Trials in four years, almost half the usual time.

“The facilities allow us to remove the variability of seasons in our research projects,” Scott says. “We can have growth in plants 24 hours a day, seven days a week, regardless of the season they’re in, enabling us to do what would otherwise be up to seven years’ worth of work within a one-year period.”

Releasing breakthroughs for adoption “in a timeframe that’s never been seen before” has become one of the hallmarks of the 21st Century.

Scott says agriculture has always had its share of early adopters – farmers prepared to embrace new and proven methods of doing things better or faster, and responding to changes in customer requirements.

“There aren’t many farmers who are still farming today the way they did 10 years ago,” he says. “And the tools that we’re hoping to produce will find a way into the hands of a farming fraternity who are equally looking for new and different ways to keep themselves moving forward.”

While the DPI has evolved since its inception 131 years ago, Scott says one thing hasn’t changed: its role in helping to solve some of the community’s more significant challenges.

“Once upon a time the big challenge was food security,” he says. “Back when our department was first started, the challenge was to come up with production systems, techniques and varieties and livestock genetics, to enable a growing colony and a growing population to be able to be self-sustaining. Obviously, we’re a long way away from that.”

Modern challenges include reducing greenhouse gas emissions, offsetting them with carbon sequestration and making progress towards net zero carbon.

There’s also the increasing prevalence of health conditions such as diabetes, nutrient deficiencies, food intolerances and allergies.

Scott says this opens up opportunities for NSW scientists using genetic tools to selectively enhance and produce new foods that can act as medicine to treat or prevent disease.

Researchers using genetic selection and gene technologies have worked with growers to successfully breed chickpea varieties that can mature in one-third of the time, avoiding frost and heat stress, and using less water.

“We can now turn our incredible science capacity to working with health professionals and coming up with solutions to some of the community’s big challenges,” Scott says. “We know primary industries have the tools, the smarts and the solutions to be able to do it, so that’s a really exciting space for us to expand into.”

Instead of adding vitamins, minerals and other additives to processed food – think Vitamin D in margarine, thiamin and folic acid in bread, or iodine in table salt – the crops themselves could produce a high performing raw food. This might include gluten-free wheat, allergen-free eggs, nuts and seeds, or fruit and vegetables containing stimulants that help the body regulate blood sugar.

Scott says another challenge will be making sure NSW DPI research also delivers benefits for the broader community, not just farmers and rural and regional communities, and addresses big picture problems such as climate change.

A run of emergencies and natural disasters – drought, bushfires, floods and the COVID-19 pandemic – in recent years has put pressure on the state government’s coffers. Also strapped for cash are universities, private research organisations and peak industry bodies experiencing a decline in statutory levies.

“We need to make sure everyone sees the merit in continuing to co-invest with industry and the federal government in providing funds for rural R&D,” Scott says. “The taxpayer and the general community are wanting to ensure that the work we do in partnership with industry is not just improving the productivity and efficiency of production systems and thereby helping farmers achieve their economic goals, but also that we’re doing so in a way that helps achieve the targets of carbon neutrality by 2030.”

Case study: breeding engagement and fishing

for talent

The Gaden Trout Hatchery, on the banks of the Thredbo River near Jindabyne, has been a popular tourist attraction for more than 50 years. Officially opened in 1953, it was run by volunteers from the Monaro Acclimatisation Society until NSW Fisheries took it over in 1959.

The hatchery breeds and grows out five species of freshwater fish for restocking the state’s inland waterways: rainbow trout, brown trout (pictured), brook trout, tiger trout and Atlantic salmon.

The key research objective is to understand the effectiveness of re-stocking with hatchery-reared trout in NSW. This includes investigating the impact of timing and fish size on the success of restocking dams and rivers for recreational fishing.

Funds from the DPI Food and Fibre Program have been earmarked for increasing the hatchery’s capacity and boosting the number of species it can house to include small native fish, such as galaxiids.

Additional funding will revitalise the visitors’ centre and enhance its value as an educational facility for schools and tourists, who can see the work involved in breeding research and take part in practical fishing clinics.

It’s a community engagement role NSW DPI Director General Scott Hansen is keen to see replicated at other research stations across the state.

“Producers can see with their own two eyes and talk to the researchers involved to understand new breakthroughs or new tools and technologies that are being produced,” he says.

“Equally, we want the local community to visit so they can keep in touch with the new things our farmers and our primary industries are doing.”

Scott says pandemic-related border closures and lockdowns have fostered a reconnection between city and country, as urban dwellers unable to travel overseas have spent more time exploring and holidaying in regional NSW.

This has provided a tremendous opportunity for agriculture to claim its identity as a modern, sophisticated data-driven industry.

“We think there are opportunities to encourage students into thinking about careers as no longer just an agricultural career, or a science, engineering, technology, teaching or arts career,” Scott says.

“Whatever career path they choose, at some stage that career path will provide valuable contributions for our primary industries sector.

“We want students to have an early appreciation of that, so it increases the chances of us getting the right people thinking about agriculture at the right stages in their career.”

ABOUT the NSW Department of primary industries (NSW DPI)

NSW DPI is the largest provider of rural R&D in Australia, with a portfolio of about $100 million annually (half externally sourced); employs more than 600 scientific and technical staff.

It injects more than $500 million into rural and regional NSW economies annually through salaries, operations, and investment in world-leading research.

NSW DPI is ranked in the top 1 per cent of institutions around the world in the fields of research in plant and animal sciences, agricultural science, and environment and ecology.

It’s also ranked 14th globally among government organisations responsible for agricultural, plant and animal science.

If you enjoyed reading this story, you might like our feature on innovations in our cotton industry.