Traditionally in Australia, the family farm has been passed on to the next generation. But…

Pests and weeds � removing unwanted guests

Every year, weeds are estimated to cost almost $5 billion in chemical control and production losses � including yield, environmental damage and grain contamination. Similar data is not readily available for insect pest control, which varies from year to year depending on seasonal conditions. As well as competition and damage to crops and pastures, weeds and insect pests are responsible for lost carrying capacity, burrs in wool, damage to hides and poisoning of livestock.

Hitting weeds for six

A 2018 report by Dr Ross McLeod, titled Annual Costs of Weeds in Australia, found the biggest burden was borne by broadacre cropping, estimated at $2.3 billion, followed by grain and livestock ($886 million) and the beef sector, with a 5 per cent decrease in productivity at an estimated cost of $462 million.

In New South Wales alone, the Department of Primary Industries estimates the agricultural economic impacts of weeds at more than $1.8 billion a year. Costs vary between regions, with Dr McLeod estimating yield loss at 0.11-0.16t per hectare across NSW, revenue loss of $25-$36 per hectare, expenditure of $129-$152 per hectare and total costs of $162-$189 per hectare.

Junee-based WeedSmart southern extension agronomist, Greg Condon, says there�s a long list of problem grass and broadleaf weeds requiring action on a regular basis, especially for farmers who have embraced minimum and no-till systems. Proactive attitudes to weed control have significantly reduced yield loss, but a consequence is the emergence of herbicide resistance.

�That incurs costs in terms of additional investment in higher cost products,� Greg says. �Generally, the lowest cost herbicides are the first to form resistance, so then you have to start paying more for those higher end and newer herbicides to control that resistant weed.�

Charles Sturt University, which has been testing weeds for herbicide resistance for more than 25 years, found about 75 per cent of annual ryegrass populations in its latest survey were resistant to Group A �fop� herbicides. The highest levels, up to 90 per cent, were found in Southern NSW. Glyphosate resistance was found in 29 per cent of the populations surveyed in the Liverpool Plains region. Resistance to herbicides has been found in 48 other weed species, including wild radish, wild oats and sow thistle.

Greg says multiple group resistance has become common, especially in ryegrass, which has encouraged farmers to adopt integrated weed management practices.

�We probably hit the wall a lot earlier than other parts of the world,� he says. �But our practice change as a consequence of that has been far more advanced than other places in the western farming world.�

Greg says integrated weed management relies on a combination of chemical and non-chemical methods, known as The Big Six.

�Farming is completely driven by compromises because you need to remain profitable at the same time,� he says. �Our mantra within WeedSmart is �More crop less weeds�. So, you�re still focused on growing a profitable crop and having a profitable farming system, but not letting weeds dictate the crop sequence or the crop choices because of resistance pressure or high weed numbers.�

The Big Six includes rotating crops and pastures, using double-knock to preserve glyphosate, mixing and rotating herbicides, stopping weed seed set, increasing crop competition, and harvest weed seed control.

Greg says reducing the bank of weed seeds is crucial, and that starts with preventing weeds from reaching maturity by using herbicides at different timings, such as a knockdown followed by pre-emergent and post-emergent applications, and late season crop-topping to stop weeds from setting seed.

�Harvest weed seed control is probably the most exciting of all of them,� he says. �It started out with windrow burning and chaff decks that allow you to put the weed seed on wheel tracks, and then the ultimate is the seed mill.�

Seed mills crush the weed seeds filtered out of grain collected by the harvester. There are now four different mills available commercially: the Harrington Seed Destructor, the Seed Terminator, the Redekop Seed Control Unit and the Tecfarm WeedHOG.

Greg says croppers in Northern NSW have led the adoption of camera-activated sensors on their sprayer booms, such as the Weed-It or WeedSeeker, to target green weeds on a brown background of fallow or stubble.

�That�s allowed them to, rather than using glyphosate all the time for example, use alternative chemistry on really low percentages of the field or the paddock,� he says. �That gives big chemical savings and the option to really alternate the chemistry.�

Another innovation, developed by a team led by University of Sydney weed research director, Dr Michael Walsh, and University of Western Australia agricultural engineer, Dr Andrew Guzzomi, is a weed chipper which uses the same camera as the Weed-It but engages a tyne to knock out weeds rather than spraying them.

�Cultivation is a really handy tool in terms of integrated weed management, but it undoes all the other benefits we�ve been striving to achieve with no-till farming,� Greg says. �You often hear people say, �Why don�t they just go back to ploughing?� but a lot of growers and the researchers behind them have looked to innovate in this space rather than just go back to the old ways of ploughing and burning. We farm in a fragile environment as it is, so why not try and innovate so you can still have those gains with no-till, but not forgo the challenges of resistant weeds. It�s a delicate balancing act.�

Greg says there also has been a lot of interest in work by researchers into more novel non-chemical tools. These include units that can deliver microwaves, steam, electrical pulses or lasers to weeds in a green crop, guided by maps generated from a boom spray, robot or drone.

Integrated pest management

Greg says there�s also a growing awareness among grain and livestock producers that blanket sprays killing all insects, including beneficial and predatory insects, are unhelpful.

�There will be times when a certain insect pest will have a big impact on a pasture and they will need to spray,� he says. �And that�s also the case in cropping where you�ve got two key times: at establishment for canola and at maturity in pulses like chickpeas and lentils.�

Greg says integrated pest management can be more difficult than integrated weed management but it�s not impossible. �We�ve got a lot of growers who are really quite focused on minimising their broad-spectrum insecticide use,� he says. �And once you can step off that intense insecticide program the beneficials build up very quickly. It�s quite remarkable, even within five years, some of the transformations we�ve seen. It�s about understanding the pests and managing the predators � recognising their value and when you might need to act above them or when you just let them be.�

NSW DPI field crop entomologist Dr Zorica Duric says a major problem with insect pests, apart from feeding damage, is their role as carriers of viruses. During 2020, large numbers of aphids were responsible for spreading bean yellow mosaic virus across faba beans in northwest NSW, where the disease caused severe damage and plant death. They also transmitted alfalfa mosaic virus into faba beans and chickpeas.

Zorica says the pests weren�t a problem during the previous drought years, but summer rain and a mild autumn were conducive to an explosion of aphids earlier than usual. They�re thought to have picked up the virus from medic in nearby pastures.

�We could see great numbers, especially of cowpea aphid, in faba bean crops,� she says. �We couldn�t see damage from virus at the time, that came later in the season.�

There�s no treatment for the virus, so Zorica says this was a case where spraying the aphids as soon as they arrived in-crop was warranted.

It�s not just crops that suffer from aphid infestations. In September, South East Local Land Services warned graziers to check stock grazing on lucerne across the Monaro, after reports of severe photosensitisation in sheep, causing permanent damage to ewes, as well as lamb deaths.

A survey found huge numbers of cowpea aphids � which produce a dangerous photo-toxin � on almost every lucerne crop in the region. Poisoned sheep developed extreme swelling and crusty lesions on their faces and the udders of lactating ewes.

There also is a looming resistance problem with insects, including those that target stored grain.

The five main pests of stored grain are the lesser grain borer, rice weevil, flat grain beetle, rust-red flour beetle and saw-toothed grain beetle.

NSW DPI research entomologist Dr Jo Holloway says insecticide resistance has been identified in flat grain beetle, mostly in grain stored by bulk handlers. The development of phosphine resistance in stored grain insects is of great concern because phosphine

is the only chemical approved for use by unlicensed operators to kill live insects.

�Phosphine really needs a sealed gas-tight storage,� Jo says. �And that�s the problem we face. A lot of the growers are using unsealed storages and if they�re really unsealed, they�re not going to kill the insects at all. If they�re partially sealed, you may develop strong resistance over time if you keep doing it.�

Jo says phosphine resistance has been found in the flat grain beetle primarily in central NSW, around Parkes, and in the lesser grain borer throughout NSW. When that happens, growers must clean out their storages, dump the seed or hire a licensed fumigator to treat it with Profume, a more expensive alternative containing sulfuryl fluoride gas.

�The good thing about grain storage is if you do it right, it should be okay,� she says. �We emphasise hygiene and, if growers can use cooling aeration, they may get away with not needing any treatment at all.�

Jo says IPM strategies are standard practice in horticulture and the cotton industry where they have led to significant reductions in chemical use. Research is continuing into the potential for targeted releases of beneficial insects into broadacre cereal crops in spring, and chemical manufacturers are working on new baits for ants, snails and slugs.

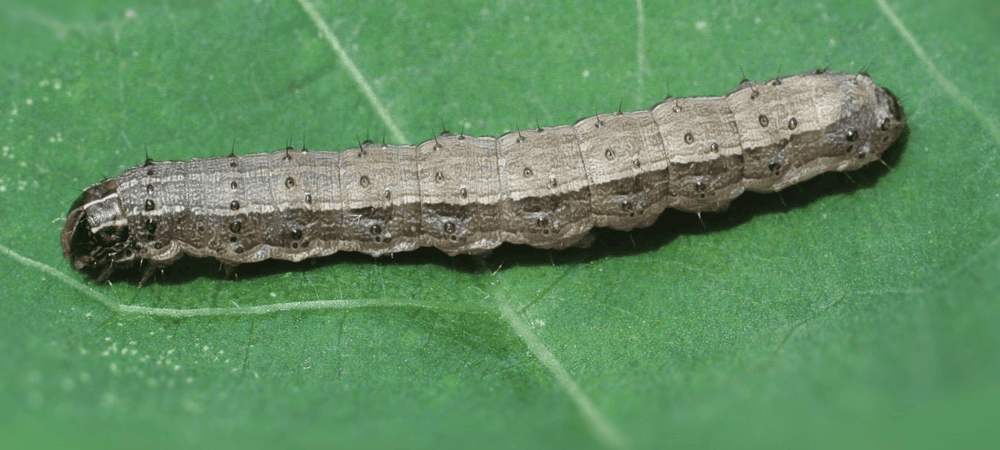

The newest pest to watch out for is fall armyworm, which was detected in a Queensland maize crop in February 2020. By November moths had been found at several locations across NSW, including the Liverpool Plains and Central West. Larvae also have been found near East Maitland in the Hunter region.

Fall armyworm poses the greatest risk to summer crops, such as corn and soybeans, cotton and sorghum.

If you enjoyed our feature on weeds and pests, you might like our story on the Varroa mite.