Scientists are concerned that the current model for stopping biosecurity threats from entering Australia is…

NSW Farmers throughout the decades

Stepping into the Honour Room in NSW Farmers� head office in St Leonards, Sydney, visitors are often surprised by the long and storied history of the�Association.

A presidents� roll from the late 1800s still hangs in the office�s meeting room, listing all Association leaders from W.H. Suttor in 1890 to James Jackson as the current President.

The birth of rural advocacy in NSW

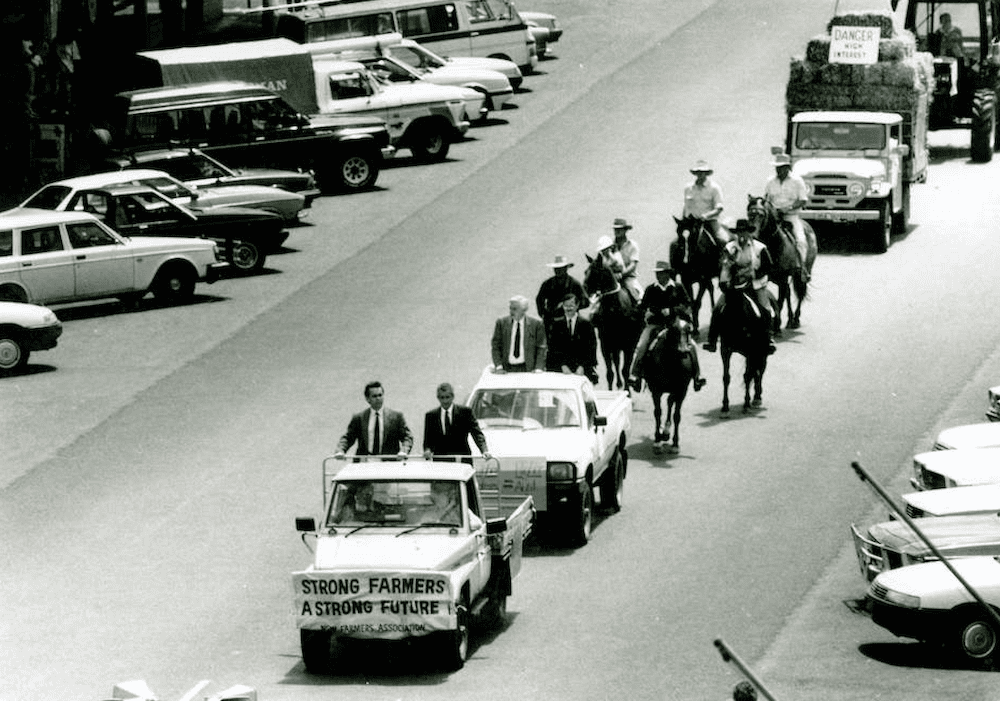

The history of NSW Farmers can be traced back to the Pastoralists� Union of NSW, which was formed in 1890 as a countermeasure to the Shearers� Union �closed shop� policy and subsequent shearers� strike. The Pastoralists� Union was ultimately successful in ending the strike, which would have prohibited Shearers� Union members from working with non-union shearers and requiring woolgrowers to hire only Union�members.

The enforcement of �freedom of contract� � the ability of growers to engage workers regardless of union status � was the first major achievement of the NSW farm sector�s advocacy body. An agreement between the Pastoralists and Shearers unions from 1891 still sits in the NSW Farmers office.

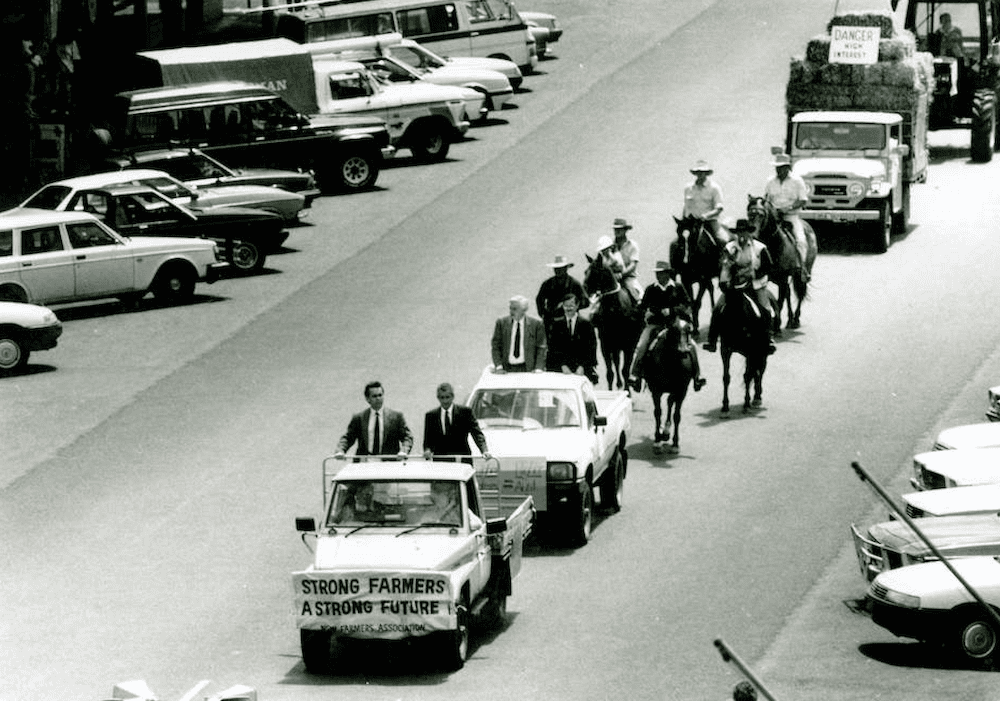

in Tamworth in 1990 against high interest and exchange rates.

The organisation was involved in the 1890 Australian Maritime Dispute when the Maritime Union refused to handle wool shorn by non-union shearers, and the dispute ended when governments took the side of employers.

The maritime and shearers� strikes led to the formation of groups that were predecessors to today�s Australian Labor Party.

Amidst a climate of strikes and industrial warfare, much of the Union�s work set the foundations for NSW Farmers as it exists today, and started a strong tradition of member volunteerism alongside professional staff.

Graziers or farmers � what�s in a name?

In 1893, the Farmers and Settlers� Association was formed to take on the Pastoralists� Union over colonial legislation that reserved large tracts of arable land for grazing, preventing small farmers from cropping.

The Association held its first meeting in Yerong Creek, where a plaque commemorating the founders was unveiled in 1999.

Tom Connors, in his book To speak with one voice: the quest by Australian farmers for federal unity, notes that the Pastoralists� Union changed their name to the Graziers� Union in 1916 in an attempt to �soften the image of an organisation established by prominent wealthy pastoralists�.

�There was rarely any controversy at a graziers� conference,� Connors says. �Delegates were usually dressed in expensive suits, many spoke with educated accents and were tactful in their remarks about politicians, public servants and farmers.

�Many delegates to farmers� conferences wore sports jackets, some were coatless, and there was a sprinkling of beards, broad Australian accents and fiery speeches.�

Moving to an apolitical system

Connors says that the graziers had a difficult time dealing with Labor politicians following the industrial fights of the 1890s; farmers generally found it easier to get along with Labor governments due to closer social attitudes and shared animosity towards graziers.

�Among farmers was a core of Labor Party supporters, although they were swamped by the majority who traditionally backed the Country Party.�

Up until the 1970s, Connors says the divide between farmers and graziers looked insurmountable, but �the desire for unity remained just below the surface�.

In bringing together farmers and graziers under a common banner, the industry needed to work to lobby on behalf of all members, across party lines.

�The election of the Whitlam Labor government changed the very nature of rural lobbying,� Connors says. �No longer could farm leaders telephone a Cabinet minister and pursue policy changes.�

With downward pressure on wool and grain prices, increasing competition from international markets, and uncertainty around quotas, farmers needed to organise professionally to talk to government about industry-wide solutions.

Livestock and grain producers flex their political muscles and become NFF

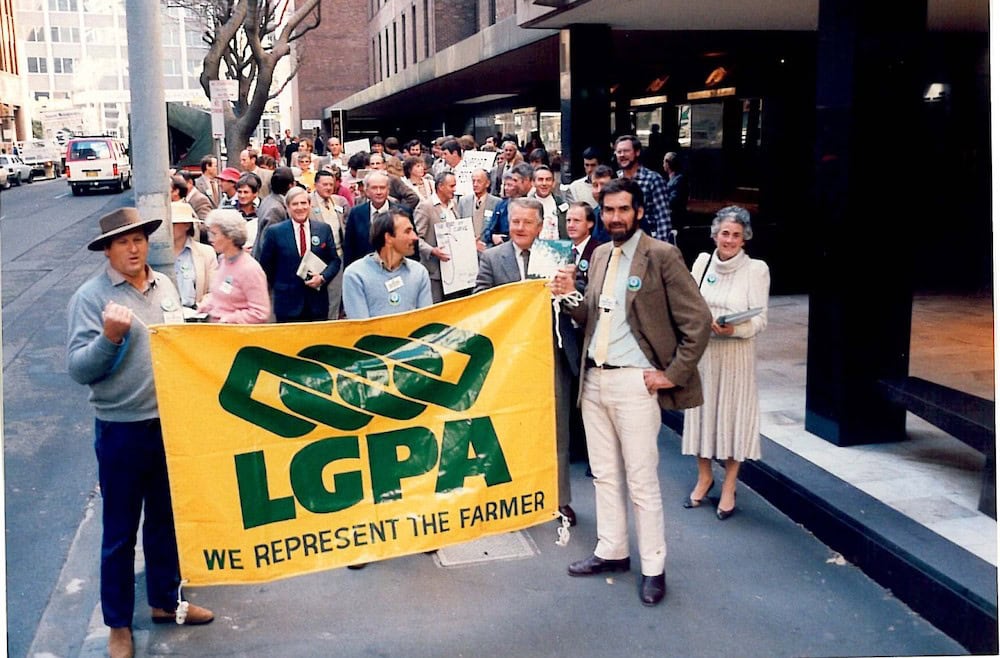

The most recent precursor to NSW Farmers was the Livestock and Grain Producers� Association (LGPA), formed in 1978.

In that year, the LPGA began holding talks with other industry bodies on establishing a national farm organisation, which became the National Farmers� Federation (NFF).

A 1982 issue of the Livestock and Grain Producer outlined major LPGA and NFF achievements, which included abolition of NSW Death Duties, tax deductibility for soil conservation, depreciation allowances on farm machinery, freight subsidies, and increases to restocking loans.

NSW Farmers was also instrumental in delivering the diesel fuel rebate, through which primary producers could claim back the fuel excise.

In 1986, the LGPA delivered a rural action plan to the Federal Government calling for reduced interest rates, floating the Australian dollar, eliminating capital gains tax, reducing tariffs, increasing funding to the Rural Adjustment Scheme, and a moratorium on rural foreclosures.

The LGPA and NFF planned a blockade of all roads into and around Canberra, as well as locally-organised rallies � a Canberra rally opposing a proposed consumption tax drew over 45,000 farmers in one of the capital�s largest ever protests.

The Federal Government took heed, and the consumption tax idea was dropped.

From the LGPA to NSW Farmers

The NSW Farmers� Association title was adopted in 1987. Chief executive John White said the new name �would identify the Association as representing all farmers, irrespective of the type of primary production in which they were engaged�.

�In the cities, the word �farmer� is now identified with courage, determination and leadership,� Mr White said.

The 1990s saw large farmer protests against high interest rates and low commodity prices, as well as the uneven playing field caused by US farm subsidies.

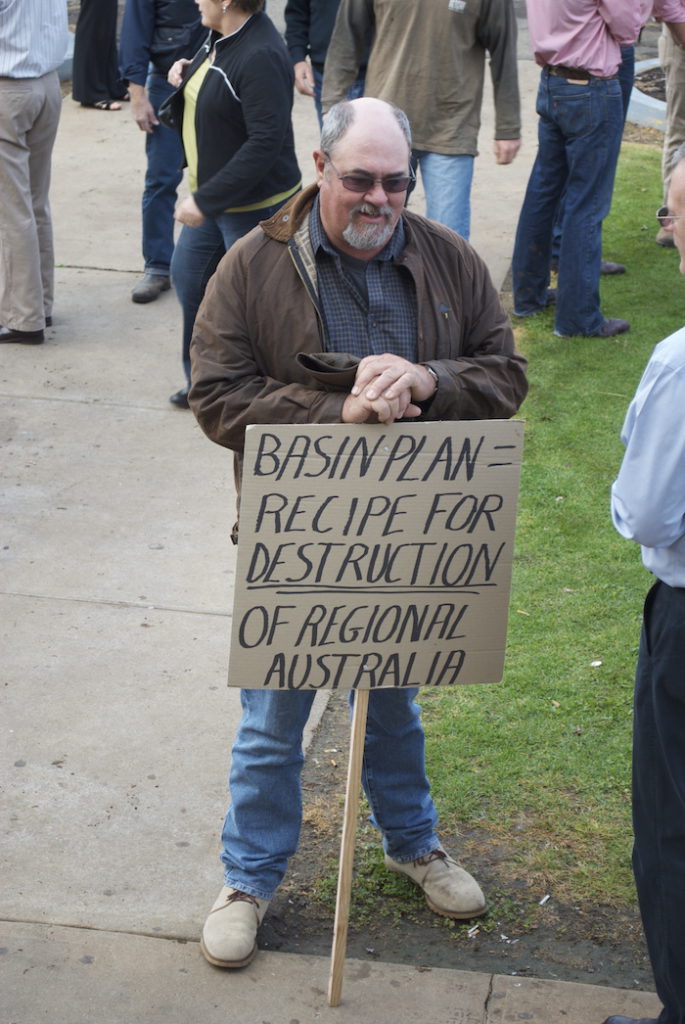

A draft of the Murray Darling Basin Plan being burned in Griffith in 2010

A farmer in Canberra at

the ‘Can the Plan’ protest

The introduction of SEPP 46 in 1995 was a rallying point for many farmers after the NSW Government introduced an overnight ban on land-clearing. The fight to overturn the SEPP would last until the start of new native vegetation codes in 2017 � a direct result of NSW Farmers� ongoing advocacy.

NSW Farmers continued the fight against tariffs, and delivered a major campaign win when the Federal Government decided not to place GST on livestock sales.

Towards a unified sector

The Association strengthened its advocacy by welcoming intensive commodity groups in the 1990s and 2000s, including oyster farmers, chicken growers, dairy farmers and pork producers.

In the early 2000s NSW Farmers successfully lobbied for collective bargaining in the dairy industry, represented farmers in water debates, fended off fee hikes on crown road enclosure permits, defended NSW research stations, and won significant workplace relations battles.

The NSW Farmers� Get off our Backs taskforce was established in 2006 to fight unfair and overburdening red tape and regulations � work that is continued by many NSW Farmers policy committees today.

Grain producers were frustrated by deregulation talks in 2008, coming out in force at Canberra rallies to support the Single Desk for wheat exports. While deregulation went ahead, NSW Farmers members made their voice heard in the halls of power.

In 2009, Peter Spencer began his hunger strike against further government actions to restrict land clearing, which brought significant public attention to farmers� ongoing concerns with the erosion of property rights.

Members were also concerned about the Murray-Darling Basin Plan and increasing coal seam gas exploration. NSW Farmers secured a landmark agreement with Santos and AGL, with the gas companies committing to honour a landholder�s right to say no to exploration on their property.

NSW Farmers continued delivering wins for members through the 2010s, including Country of Origin Labelling, primary industries education, drought support, inland rail, multi-peril crop insurance, and codes of conduct for the horticulture and dairy industries.

An eye to the future

In 1998, NSW Farmers Youthlink � the precursor to NSW Young Farmers � held a �Farmers Toward 2020� forum, where they delivered the following forecast:

�That 2020 will be a dynamic and exciting time for agriculture. Farmers will be profitable, well-educated, adaptable, self-determining, and capable of carrying out economically, socially and environmentally sustainable practices.�

“It�s a forecast that could be dubbed a self-fulfilling prophecy,� says Rachel Nicoll, current chair of the NSW Young Farmer Council. �Not only is it a thoughtful curation of its time, but it carries as much weight today, so far as demonstrating the excitement and curiosity about the possibilities of the future in�agriculture.

It�s not just the big wins

Looking back at what NSW Farmers has achieved, James Jackson says that it�s not always about making something happen � sometimes it�s stopping things from happening.

�You like all of your policy development to be proactive, but by the very nature of policy, you have to react to what others put on the table � including government,� he says. �There are things they haven�t thought through that well, like the koala SEPP, that have inadvertent consequences for agriculture.�

While the Association has delivered some landmark wins, James recognises that it�s not always about the major headlines. �A lot of small wins make up some big achievements for the Association.�

If you enjoyed our story on the history of NSW Farmers, you might like our features on the past winners of Farmer of the Year.