The pastoral town of Ivanhoe was headed for a deep slumber in 2020 after a…

In defence of modern agriculture: is the �old way� always better?�

Years ago, I was in a book club and the inaugural book chosen by a friend was The Third Plate by American chef Dan Barber. This book had garnered rave reviews as a critique of modern food systems and had been chosen by my friend who wanted to learn more about where his food came from. While this book is an entertaining description of his restaurant, dispersed with stories of where particular high-end food products come from, it also represents how celebrity and fallacy dominate messaging about where food comes from. For example, the book begins with an anecdote about a farmer who suddenly develops weakness in his arms after spraying a chemical called 2,4-D. Doctors were not able to diagnose his ailment, so he switched to organic farming. This contradicts all known toxicology data on 2,4-D and Barber provides zero factual sources.

The view that has been popularised is simple: chemicals, fertilisers, and GMOs = bad; organics = good. Commentators such as Barber have espoused the view that sustainable food must be organic, local, and small, rather than large and industrial. This is akin to agriculture in the developing world. Farmers are organic because they cannot afford fertiliser, their food is local because of poor supply chains, and farms are small scale because they are not profitable enough to invest in any improvements. It is no coincidence that nations with food systems with these characteristics are food insecure.

Consumers not only want food to be tasty, safe, nutritious, and affordable; they want it to come from farms that protect the natural environment, respect the welfare of animals, help sustain rural communities, and provide workers with fair conditions. An organic, local, and small food system would mean ignoring a century of science, would force farmers to work harder for less income, would give consumers fewer food choices, and the natural environment would in fact be worse off.

At university, I went on a study tour of The Philippines, seeing how smallholder farmers operate. These farmers were extremely satisfied with the adoption of GM corn, which had improved their productivity and profitability through decreasing their use of pesticides, which had also brought about environmental benefits. One additional important outcome was that the farmers did not have to work as hard to manage their pests, so had more time to spend with their families.

This good news about science-based farming, however, has been difficult to communicate to the developed world, where a litany of food writers, journalists, and commentators have found widespread acclaim in promoting pre-industrial alternatives. One of these food writers, Michael Pollan, said the following about the frighteningly uncritical support he has gained:

�The media has really been on our side for the most part. I know this from writing for the New York Times, where I�ve written about a lot of other topics,

but when I wrote about food I never had to give equal time to the other side. I could say whatever I thought � so I felt like I got a free ride for a long time�.

There is a lack of understanding by the Australian public of where their food comes from, and it is in this vacuum that pseudoscience and emotional stories have filled the informational void. For example, a 2014 study of over 1,400 Australian children revealed that 92 per cent didn�t know bananas grew on plants.

So let us give weight to the other side and recognise the advancements that have been made by agriculture which allow us to enjoy safe, affordable, and nutritious food that is the most sustainably produced in the world. Precision farming has made possible the production of more food while using less land, less water, and fewer chemicals, implying large benefits to the natural environment.

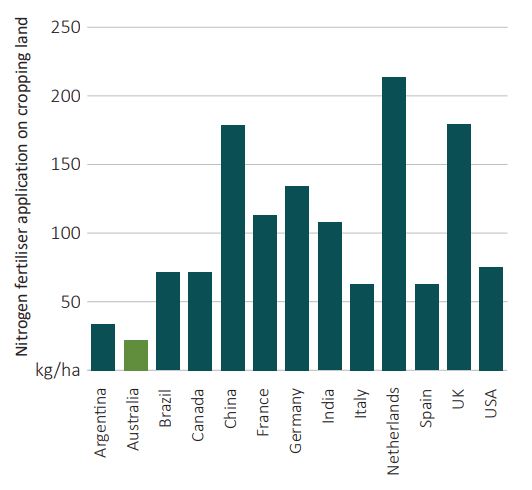

Firstly, Australia has the highest rates of adoption of no-till farming in the world, with 84 per cent of farmers retaining stubble and protecting their soils. Australia has some of the lowest rates of nitrogen fertiliser and pesticide application in the world, with 68 per cent of farmers optimising their use so as to reduce their reliance. The sector has even reduced emissions by 20 per cent over the last 30 years.

Figure 1: Nitrogen fertiliser application rates of selected OECD countries

Australian agriculture has also had to contend with deteriorating seasonal conditions due to climate change. Gains in productivity have offset the negative effects of climate change over the past 30 years, so that actual productivity levels have still increased. For example, wheat yields under dry conditions have increased by 14 per cent since 2008 as technology and management practices have changed.

These advancements in productivity and the greater intensity of modern agriculture have allowed Australia to shift land use into nature conservation while still producing more food. From 1970 to 2020, agricultural output increased by 104 per cent while land used by agriculture fell by 28 per cent.

TAKING OFF: From 1970 to 2020, agricultural output increased by 104 per cent while land used by agriculture fell by 28 per cent. R&D continues to yield high returns, with estimates indicating that each additional $1 of investment generates a return of $7.82 for farmers.

If we switched to earlier production methods to meet the market demands of today, the cultivated area for food production would have to increase enormously, leading to much greater levels of deforestation. A study in 2019, for example, calculated that if England and Wales made a switch to 100 per cent organic farming, average national crop yields would fall by 40 per cent, and greenhouse emissions would increase by 21 per cent. There would also be the implications of needing to clear more land and increase food imports to feed the population, as well as increasing food prices. This is hardly good for people or the planet.

If we really want to continue to improve our food systems to make them more productive and better for the environment there needs to be a renewed trust and focus on science and R&D. This area continues to yield high returns, with estimates indicating that each additional $1 of investment generates a return of $7.82 for farmers.

There also needs to be a strong movement towards outcomes-based certifications and production standards which can assist consumers to make choices that actually benefit the environment. There is a real chance to properly define regenerative agriculture and make this the science-based standard for industry to follow. This will incentivise farmers to adopt sustainable production practices, allow the industry to demonstrate its sustainability credentials to trading partners, and educate consumers on the benefits that come from science-based agricultural production.