Traditionally in Australia, the family farm has been passed on to the next generation. But…

Seed singulation reinvented

High-speed precision planters capable of placing a corn seed the right way up and at the correct angle are a reality, and the implications for crop yield benefit is making this technology increasingly viable. It�s a part of the slow evolution of mechanised seed singulation, which has been around for 50 years and is now lurching towards narrow-row winter crops, where the inexact air seeder is king.

An air seeder scratches a channel in the dirt and a bunch of seeds are blown down tubes into them, some clumped together, some spaced far apart. The Grains Research and Development Corporation says the success rate of emergence using that methodology varies from 50-85 per cent but the trade-off is seeders can be configured for narrow rows which equates to more yield per hectare.

Good enough to turn a dollar, given the relative low cost of seeds and equipment to achieve that result. But given a choice, a farmer would want the successful emergence figure to be north of 90 per cent � and seed singulation with a high-speed precision planter makes that possible.

How seed singulation works

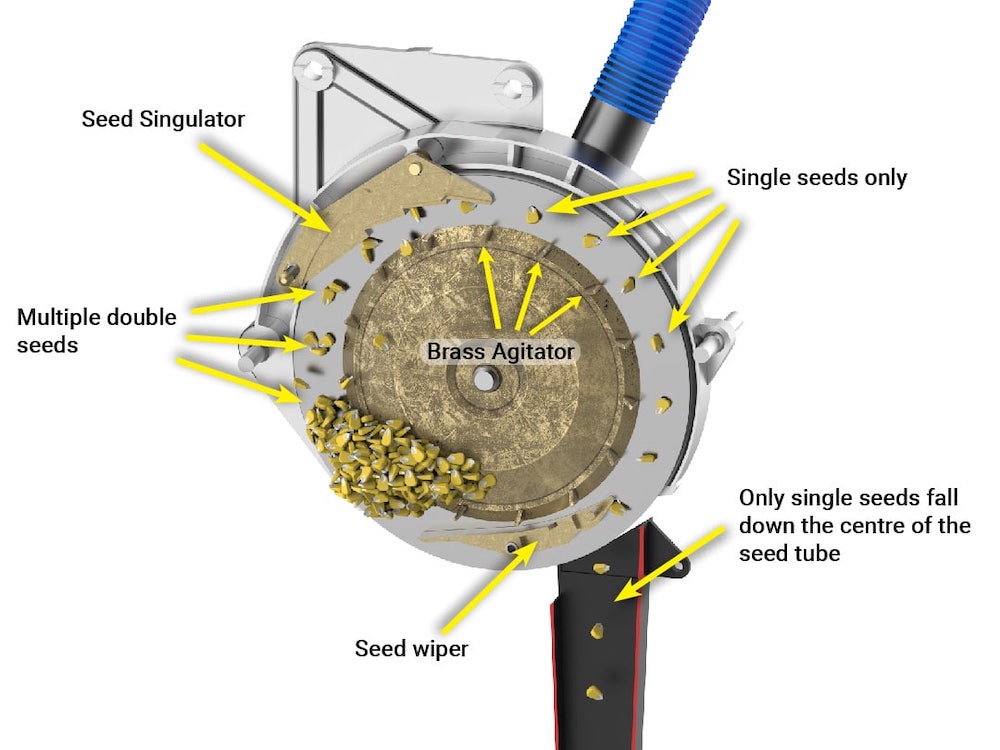

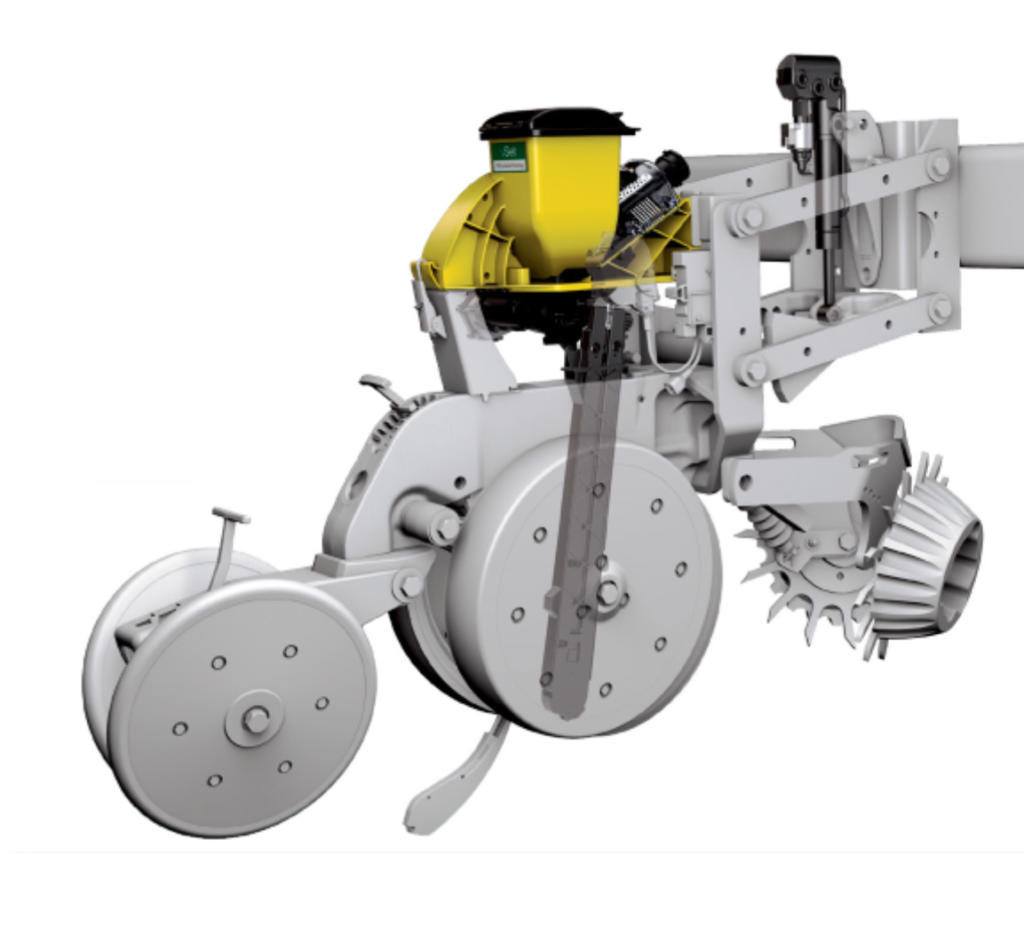

The way it works is that seeds from the main seed cart are blown into smaller seed boxes which sit above the soil opener and have a metering system inside. The metering system is typically a rotating disc plate with holes into which seeds are held (usually by vacuum) until they pass over a delivery tube. The vacuum is blocked at that point and the seed falls down the delivery tube into the furrow at a set distance from the previous seed.

It�s a system already common in maize, sorghum, cotton and sunflower crops, and there have been excellent results in canola. The next frontier is making it work in the narrow rows of winter grain crops, and advancements in sensor technology are starting to make it more viable.

US seed singulation specialist Precision Planting has been at the cutting edge of the technology for many years, using advancements in sensor technology to measure soil moisture, temperature, electrical conductivity and organic residue with a light spectrum.

It�s all done on the fly so that when coupled with adjustable depth controls, the seeder can plant at the exact depth for maximum yield potential. It comes at a cost and in summer crops, where rows can be much wider, yield gains are more apparent.

�The cost benefits are clearly there in the wider summer crop rows, but it would take longer to recover the cost of investment in winter crops,� says Anthony Martin, who has been experimenting with seed singulation in winter crops at Mullaley near Gunnedah.

The simple reason for the added cost is the number and physical width of the seed metering boxes which sit above each soil opener. Each unit comes at a premium and trying to squeeze them into the sub-40cm row spacing idyll for a winter crop is less than practical.

But Anthony has been giving it a go, working with Precision Planting to trial a variety of winter crops on his minimum till, controlled traffic farming operation.

�We want to move to singulation in all grains and have been planting winter crops of legumes, cereals and canola,� he explains. �We�ve been using the planter at 50cm row spacing but it�s a bit on the wide side for cereals. It just needs to be a bit narrower.

�Yield was still good at 50cm but that was offset by the cost of weed suppression and surface protection from the sun.�

Wider channels between the rows means less competition for weeds while the sun dries out the soil because it�s not covered by the canopy. Anthony is confident that if these issues could be solved, the yield benefits would outweigh the costs.

�The system we used singulated bread wheat perfectly,� he says, �but it wasn�t quite as good on durham, while in canola we got a bit of static electricity on the disc plate which is solvable with an additive.�

�Once we solved the static electricity issue, we go very high singulation in canola � around 95 per cent of single seeds. Mung beans and chickpeas got high 90s, while in sorghum we got as high as 99 per cent.�

So why is seed singulation so important?

David McGavin from Precision Seeding Solutions says it�s all about giving each seed � some of which are getting more expensive as hybridisation becomes more of a reality � the best chance to grow.

�There�s a huge difference between a precise machine and one that does an okay job,� he explains. �We�re talking another third because if you were to look closely at a row of air-seeded grain, you�d get rid of 30 per cent of it.

�When two seeds are dropped into the row together, there is no benefit. They are competing for moisture and nutrients which handicaps their ability to get a good start, so you end up with two spindly plants which affects grain size.�

He admits the cost of going to narrow-row spacing gets in the way of realistic adoption of seed singulation in winter crops, but still believes there are gains to be made.

�Yield benefits can be anywhere from 2-5 per cent which is still big dollar returns depending on area,� he says. �One customer planted 137ha in sorghum and achieved half-a-bale yield difference, which is about 3 per cent increase.�

Perhaps not the figures to start a revolution, but as communication technology in machines advances, David says it will become more viable.

�The smartest thing we�re doing is taking moisture and soil type readings and from that, determining the depth the seed needs to be to optimise seed germination,� he says. �With hydraulic depth control, the system will automatically adjust depth on the fly.�

Martin says he�d love to have the money to invest in that level of technology, but even without it believes there are still benefits in singulating winter crops.

�I�ve seen trials in the US where machines are planting corn seeds up the right way so they don�t come up late and with the right orientation to the row so the leaves grow 90 degrees to the direction of the row for the best light inception. That�s pretty amazing.�

The Deere vs AGCO heavyweight bout

An indication that precision planting with seed singulation and delivery systems is expected to become widely used by row-crop farmers is the legal intervention which saved it from becoming monopolised in the ag marketplace.

In 2017, the US Department of Justice stepped to block John Deere�s bid to purchase the Precision Planting company. Deere already had 44 per cent of the high-speed singulation market with its seeders, and because Precision Planting had a 42 per cent share of the market, the DoJ reckoned that was just a bit too greedy because �high-speed precision planting technology is expected to become the industry standard in the coming years�.

This gifted Precision Planting to rival global giant AGCO which then found itself in a well-publicised patent punch-up with Deere over similarities between the two precision planting systems.

When you consider (according to Goldman Sachs in 2016) there�s a potential 70 per cent improvement in farm yields by 2050 and $240 billion to be made in ag tech with this kind of technology, you can understand why it is a hotly contested space.