Sponsored by iinputs

The agricultural legacy of James Ruse

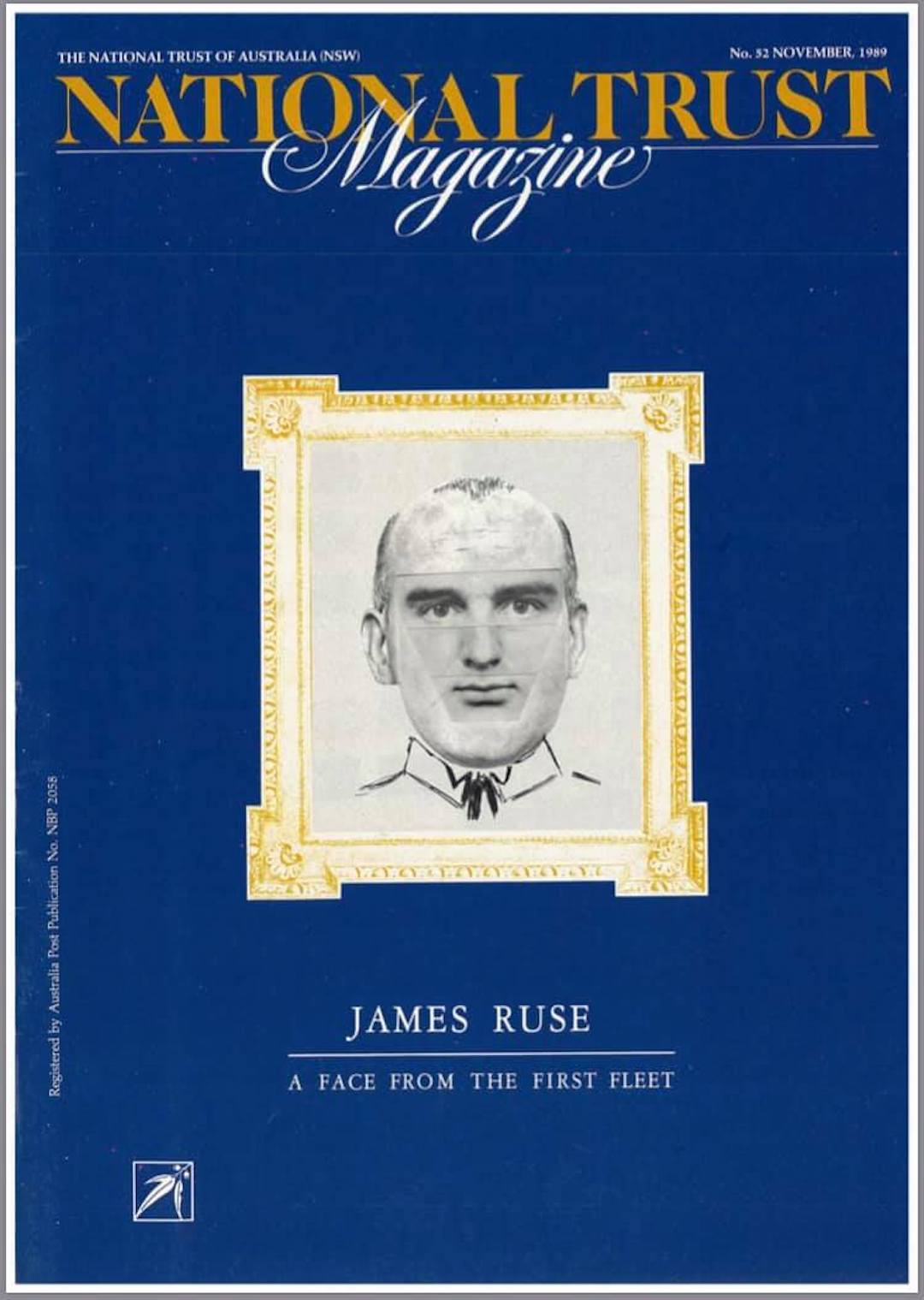

The remarkable tale of James Ruse is one of a convict turned agricultural trailblazer, whose perseverance and innovation laid the foundation for farming in early colonial Australia.�

Lauded as Australia�s first successful settled farmer, James Ruse worked hard to turn his life around after arriving at Port Jackson with the First Fleet on the convict ship Scarborough.

Indeed, according to various historical accounts and biographies, Ruse notched up a long list of firsts along the way.

Ruse was reputedly the first prisoner ashore, piggybacking an officer to the beach to keep his boots dry. He later became Australia�s first settled farmer, the first ex-convict to be granted land at Parramatta and the first settler to become self-sufficient.

A farm labourer and married father of two, James Ruse was 23 when he was convicted of burglary in the Cornwall Assizes � the equivalent of the NSW Supreme Court � and sentenced to death by hanging. This was commuted to seven years and he was originally to be transported to Africa.

After spending more than four years in the prison ship Dunkirk moored at Plymouth, Ruse was transferred to the Scarborough which left England with the rest of the First Fleet in 1787.

Trials, tribulations and triumph

Journals kept by British marine commander Captain Watkin Tench record the difficulties encountered by the early settlers, including the failure of vegetable and grain crops because of drought, a lack of suitable tools, and the absence of livestock manure to improve the barren soils near Sydney.

The Government Farm worked by convicts was abandoned and over the next two years rations of flour, salted pork, butter and dried peas brought out on the ships dwindled as the colony waited for more supplies to arrive.

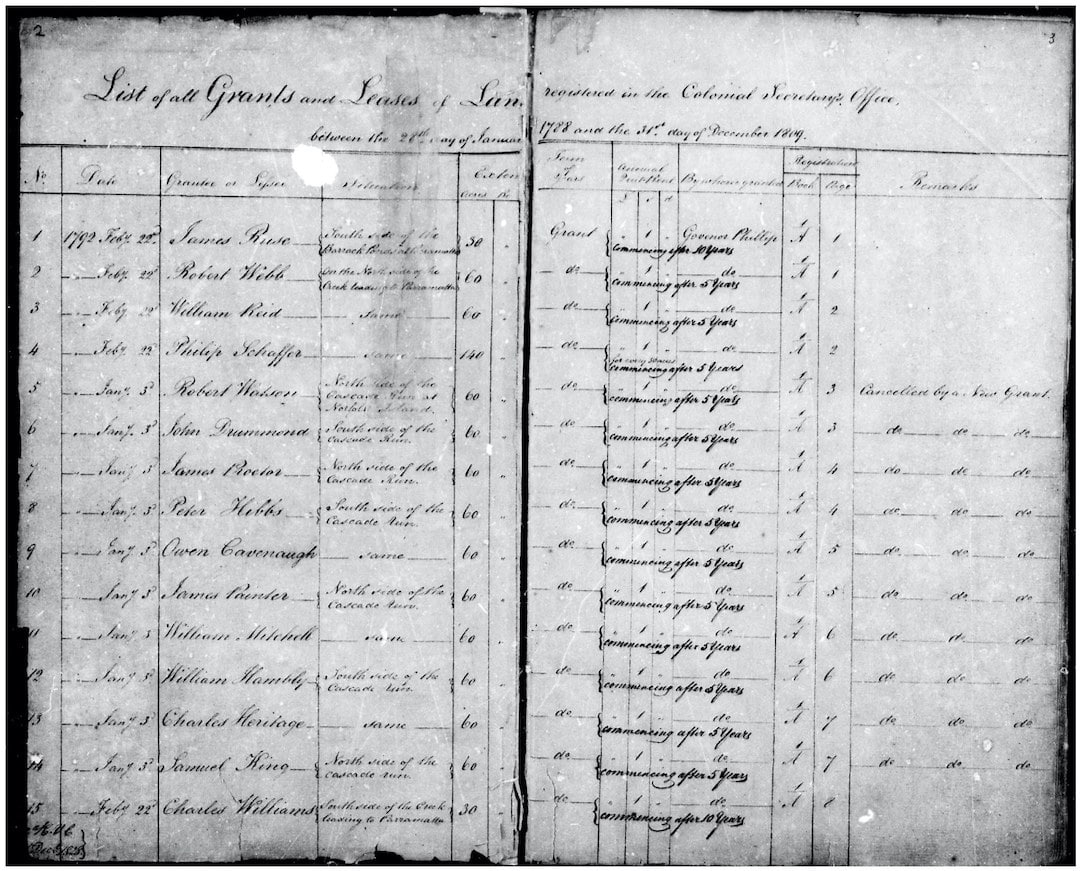

After Ruse completed his sentence, Governor Arthur Phillip awarded him land at Rosehill in December 1789, which he cleared with the aid of convicts. He was also given seed, tools, six hens and two pigs.

Almost a year later, Tench was part of a survey of Rosehill and the Parramatta River when he visited Ruse and recorded his story.

Ruse described burning the fallen timber, digging in the ashes and hoeing it up, before clod moulding it and digging in the grass and weeds.

�This I think is almost equal to ploughing,� Ruse told him.

�I then let it lie as long as I could, exposed to air and sun; and just before I sowed my seed, turned it all up afresh. When I shall have reaped my crop, I propose to hoe it again, and harrow it fine, and then sow it with turnip-seed, which will mellow and prepare it for next year.�

By then Ruse had married Elizabeth Parry, the first female convict to be emancipated, describing her to Tench as �industrious�.

Their crops included 1.5 acres of bearded wheat � sown at 3 bushels of seed (27.2kg), he expected to reap 12 to 13 bushels (326-354kg) � as well as 0.5 acres of maize and a small kitchen garden.

Ruse planned to bury the crop straw in pits to make compost, but warned that even with the �middling, neither good or bad� soil on the farm, it would fail without cattle to produce manure for enriching the soil.

The first crops yielded only enough grain to provide seed but Ruse had proven it was possible to become self-sufficient and he was rewarded with a grant of 30 acres, known as Experiment Farm, on the lands of the Burramatta Dharug people.

Tench visited Experiment Farm in December 1991, reporting that Ruse lived in �a comfortable brick house, built for him by the governor�. He had 11.5 acres under cultivation which would be sown to maize because it yielded better than wheat, four breeding sows and 30 chickens.

But after a catastrophic harvest two years later, Ruse sold the farm to a neighbour, Surgeon John Harris, and obtained a new grant of 30 acres on the Hawkesbury River flats.

The family prospered on the fertile land at the junction of South Creek, sometimes known as Ruse�s Creek, and the Hawkesbury � now Pitt Town Bottoms � until repeated floods drove them into debt.

Ruse went to sea, working on whalers and cargo ships, while his wife Elizabeth held down the fort at home.

In 1806 she was listed in the Muster � the 19th Century equivalent of a census � as a landholder with 15 acres, three workers, seven pigs and supporting four children.

For many years historians thought the Ruses, who had five children of their own, had adopted two more, Ann and William.

But descendants used DNA testing to prove in 2019 that Ann and William were the offspring of Elizabeth and James Kiss, a friend of James Ruse.

After further flooding, Ruse surrendered the land on the Hawkesbury and successfully requested a grant of 100 acres at Salt Pan Creek in the Bankstown area.

By 1813 he owned a house at Windsor and in partnership with Elizabeth later bought a half share in a farm on the Hawkesbury, before taking up grants of 100 acres each at Bankstown and Riverstone.�

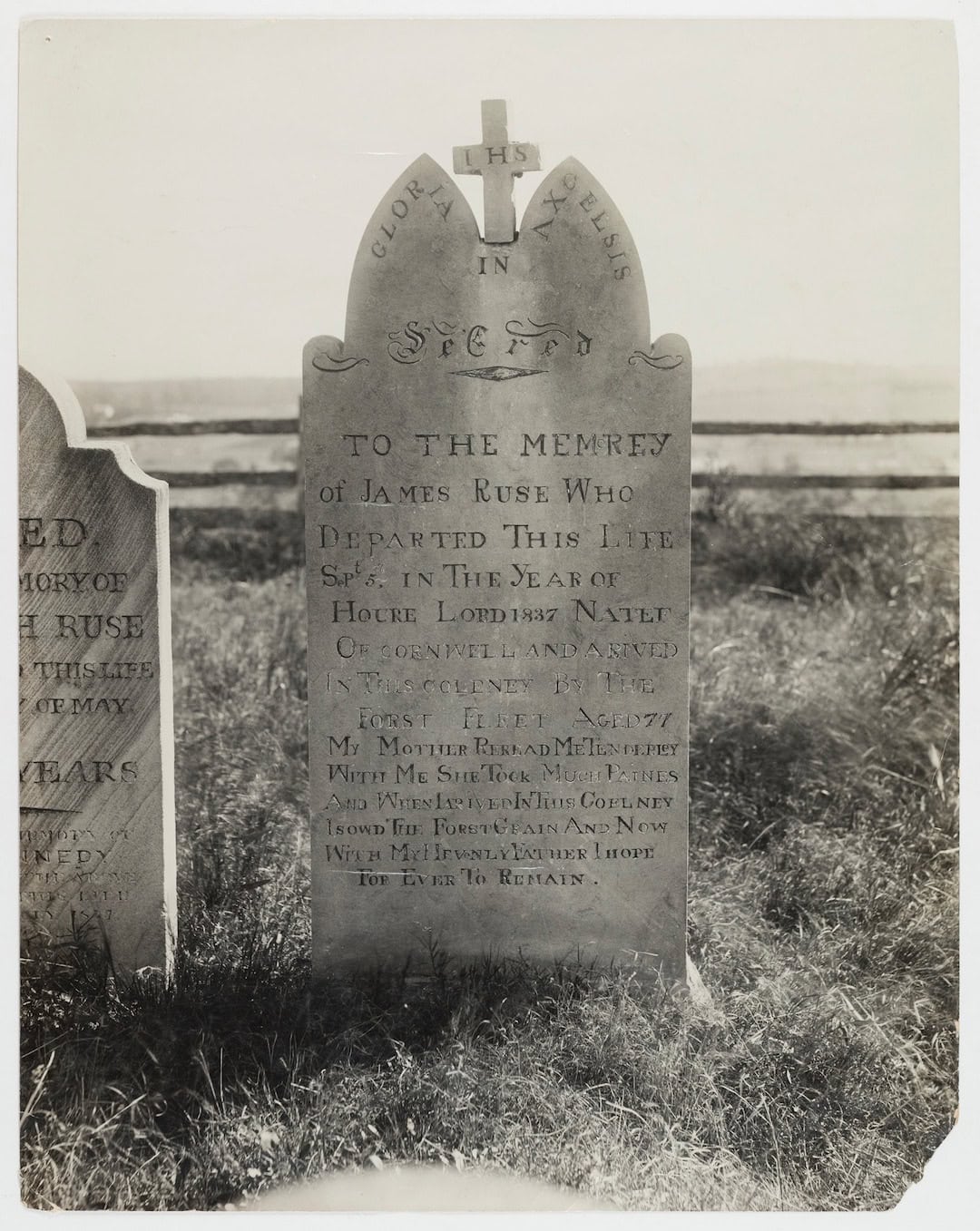

The final grant in 1821 was at lower Minto � now Macquarie Fields � where the couple remained until their deaths: Elizabeth in 1836 and James 18 months later after carving the epitaph for his headstone.

Using a hand chisel he inscribed the words:

Gloria in axcelsis

Sacred

To the memerey of James Ruse who departed this life Sept 5th in the year of houre Lord 1837 Natef of Cornwell and arived in this coleney by the forst fleet aged 77

My Mother reread me tenderely with me she took much paines and when I arived in this coelney I sowd the forst gran and now with my hevenly father I hope for ever to remain.

Ruse was buried beside Elizabeth in St John�s Catholic Cemetery, at Campbelltown.

After vandals caused damage at the cemetery in 1994 his headstone was taken for safe keeping to the council-owned Glenalvon House, home of the Campbelltown and Airds Historical Society, and a replica erected in its place.

It wasn�t until a century after Ruse�s first successful harvest that the Department of Agriculture was founded, with experimental farms established in 1892. The first wheat research started in 1893 with trials of 200 varieties planted at Wagga Wagga.

In the following years, Ruse�s exploits were idealised in the jolly language of the time for

the benefit of school children learning about Australian history.

Remembering Ruse

Alison Hay wrote in The School Magazine in August 1947 that Ruse had been sent to Australia as a convict after doing �some little foolish thing�.

�For this young, brave farmer, the first months on his little farm were the hardest,� she wrote.

�Kangaroos and wallabies ate the young green wheat, thieves stole his cabbages by night… He was tired, often very short of food, and very lonely, but he never gave up.�

And in an article in Walkabout magazine in 1964, Clifford Tolchard wrote that Ruse was probably mistaken in thinking he had sown the first grain as he had claimed on his headstone.

�But in his humbler sphere Ruse left his mark on Australian history as surely as did the more exalted figures of the civil and military leaders,� Tolchard argued.

�It is fitting that the James Ruse Agricultural High School at Carlingford should be named after the man who was, after all, the first true farmer in Australia.�

Concluding James Ruse�s entry in Volume 2 of the Australian Dictionary of Biography published in 1967, BH Fletcher wrote Ruse was �one whose importance in New South Wales history has been unduly exaggerated and romanticized. Although his early achievements were noteworthy, he soon faded into the background and led an existence that scarcely distinguished him from many of his associates.�

Fletcher might have been obliquely referring, among others, to Lieutenant John Macarthur, who established Elizabeth Farm on 100 acres granted at Parramatta in 1793 and is widely regarded as the founder of Australia�s wool industry.

Nonetheless, Ruse�s persistence, despite countless setbacks from drought, bushfires, floods, thieves and pests, demonstrated it was possible for settlers to successfully farm the land.

The original little Aussie battler pioneered cropping in NSW and set an example for generations to come.

His name was not only given to James Ruse Agricultural High School, which was established in 1959, but also the suburb of Ruse in 1968 and the Parramatta bypass, James Ruse Drive, in 1981.

Sources: Australian Dictionary of Biography, First Fleet Fellowship, Gutenberg, Launceston Then, James Ruse Agricultural High School, National Library of Australia (Trove), State Library of NSW, The Stony Ground: The Remembered Life of Convict James Ruse (2018) Michael Crowley, People Australia, James Ruse: The Humble Adventurer, Walkabout (1964) Clifford Tolchard

To read about the Tenterfield Saddler, an iconic Aussie landmark, click here.