Twelve dogs from across Australia are gearing up to compete in the Cobber Challenge to…

Big corps & small towns working together

This story was researched and written as the New South Wales government progressively locked down local government areas across NSW as day by day, the numbers of people affected by coronavirus steadily rose.

So, there was no getting away from the contrast between urban and regional NSW.

With agriculture deemed an essential service, rural agribusinesses have been able to retain workers and continue operating, albeit with certain modifications at times.

Interviewed for What�s Your Beef (The Farmer, May-June 2021) John Seccombe � Chair of the Northern Cooperative Meat Company � said the pandemic required abattoirs to change workplace practices to reduce close interaction between employees. And in July this year, the Nestl� factory at Blayney underwent a deep clean after a worker interacted with a tier one contact from one of Sydney�s local government areas. The alert led to a short lockdown in the Orange district.

But it was unnecessary to compare the freedoms of living in regional NSW, and, in particular, on rural blocks of land. As far as the pandemic goes, agriculture is a protected industry, but it relies on an available and skilled workforce.

The security of the industry is on the back of last year�s release of NSW Farmers Association�s blueprint for the future of agriculture, loosely referred to as �30 by 30�, or more accurately, Growing Our Food and Fibre Future.

The �30 by 30� document clearly identifies a pathway to increased economic prosperity for NSW agriculture � positioning the State as a powerhouse of agricultural production contributing $30 billion towards the national goal of $100 billion by 2030.

To deliver on that goal, and support the growth of population centres, the NSW government needs to invest in infrastructure and, as identified in Whose Land Is It Anyway? (The Farmer May-June 2021), create consistent legislation around land use planning.

And in the July-August 2021 issue of The Farmer, in the Suing For Paradise article, the dynamic views surrounding mining, particularly open-cut mining, were analysed.

There was plenty written last year in mainstream media about the trend for people to move into the regions as remote working became more commonplace and their workplaces supported and enabled them to choose where to live. For many, their decision was to move into population centres where people didn�t live in crowded communities.

But this is not a new situation.

Infrastructure and big business

Infrastructure is key to enabling economic and population growth and the �30 by 30� document clearly demonstrates that those key outcomes will help drive agriculture as a powerhouse of the NSW economy. Along the way, agriculture will help build a workforce in a state with an employment rate that is too high � the second-highest in Australia at 5.1 per cent (June 2021). The youth unemployment rate for 15-24 year olds was 13 per cent (January 2021, ABARES data).

In NSW�s Central West district, unemployment in January 2021 was 4 per cent, with youth unemployment at 8 per cent. ABARES reported workforce participation in the Central West district was 68 per cent, compared to a State-wide rate of 65 per cent. Workforce participation is based on a minimum of one working hour per week.

When people of working age move to a region, many of them have families and want schools, health care, secure employment opportunities, and reliable transport routes. In the same way, employers want schools, health care facilities, and reliable transport routes to be built and maintained, in order to attract employees.

The Central West population is 156,000 people, with the major towns of Bathurst, Blayney, Cowra, Lithgow, Molong, Mudgee, Oberon and Orange, across an area of approximately 31,365 km2. The NSW Department of Planning and Environment has projected the population of Bathurst will swell to 51,550, Dubbo to 46,500 and Orange to 46,250 people, by 2031.

Orange currently has a population of more than 40,500 people and the council is a key partner in driving economic growth, including lobbying the NSW and Commonwealth governments for infrastructure to enable that growth. Of course, decentralisation has been a key corridor for growth in NSW and in January 1992, Orange became the headquarters of the Department of Agriculture.

Since then, the town has attracted growth in medical facilities and schools, corporate organisations have moved into Orange and other Central West towns, and the airport and other transport routes are key parts of economic growth for the region.

�We now have the headquarters of Paraway Pastoral Company, Rabobank Australia and the Rural Investment Corporation in Orange,� says Orange Mayor and NSW Farmer�s member, Reg Kidd.

�From 2022, UGL (a large engineering company) will operate their transport hub out of Orange. Taking over from John Holland Rail, UGL will be responsible for operating the Country Regional Network � almost 1000 kilometres of the network is dedicated to moving grain, from the silo to local markets and ports for export.�

Orange Mayor and NSW Farmer�s member, Reg Kidd.

Because of the major agricultural and infrastructure investment vehicles that chose to locate in Orange, private research and extension services have developed.

Bioscience company, Agritechnology has established its presence in nearby Borenore. The universities of Western Sydney and Newcastle have joined Charles Sturt University in the region. Orange Agricultural Institute is an established 700 acre education and extension facility, meeting the needs of regional farmers.

Supporting public and private hospitals in the district, CSU recently expanded its health courses to include medicine alongside dentistry, physiotherapy, pharmacy, nursing and science. But there�s more.

�CSU also offers degrees in engineering, IT, teaching, and agriculture,� Reg says. �When Newcrest Mining expanded into the region they began supporting some of our young people with scholarships to study accounting and engineering. They provide apprenticeships at both Cadia Valley and Bathurst, and employment opportunities locally and elsewhere.

�Young people choose to work in mines closer to towns like in our region, where they have a 15-minute commute to work, and can be home for sport and other community activities.�

Reg Kidd, Mayor of Orange City Council.

Unfortunately, unlike many of its neighbours, Orange has limited opportunities to expand its water storage infrastructure.

But Reg sees this as an opportunity for the region to invest in new technologies for recycling water, and encouraging residents to engage in shared environmental values by creating new habits around water use.

Employment for locals and new residents

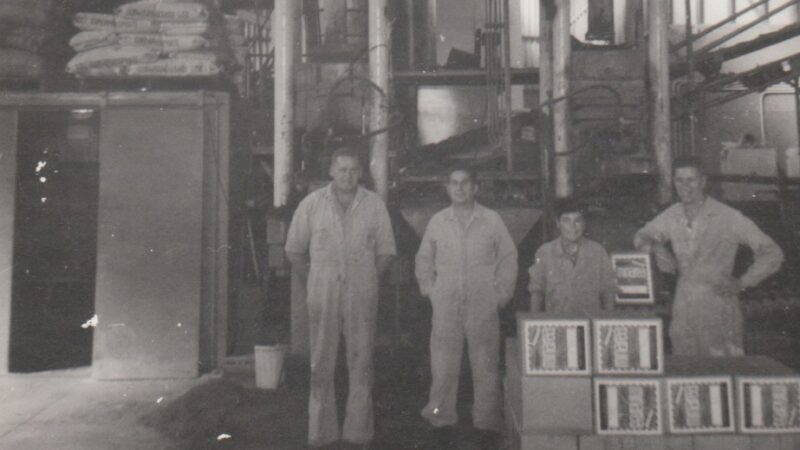

Further afield, but still in the Tablelands region, in the past 10 years, Nestl� has invested $200 million in its Blayney site, where it manufactures Nestl� Purina PetCare pet food. According to factory manager at Blayney, Andrew Devlin, more than 80 per cent of raw materials used in manufacturing pet food are sourced from the local region, including meat and grain, supporting 60 local businesses in western NSW. Nestl� exported more than $45 million of pet food in 2019.

In east-central NSW, the national logistics hub operates out of Parkes Shire � the announcement in July of a $10 billion investment to construct the Melbourne to Brisbane Inland Rail further positions the region as a development hub for the supporting logistics of manufacturing, warehousing and distribution centres.

Parkes is a key location for redeveloping efficiencies around inland rail for NSW agriculture; the NSW government�s investment aligns with NSW

Farmers focus in the �30 by 30� document to build transport infrastructure that supports agricultural production � efficiently moving machinery and product around the State, interstate and to ports for export. About 1,500 hectares of land will be available for development, and up to 3,000 jobs are expected to be created.

One of Australia�s well-known wineries, De Bortoli Wines, has its footprint squarely in rural NSW. The family-run agribusiness is still central to Bilbul, in the Riverina, with vineyards, a cellar door, and broadacre cropping.

Over time it has expanded across NSW�s Hunter Valley, and into Rutherglen and the Yarra Valley in Victoria. For NSWFA member, and Managing Director Darren De Bortoli, the values that have attracted the company�s investment in each region are key tourist markets, reliable transport routes and infrastructure with direct access to export facilities, workforce and water.

�Regional towns are untenable when their economies and workforces are reliant on only one industry. Our closest regional town is Griffith and most of our workforce live there. Having viable agricultural industries in a region attracts other investors into towns � manufacturing equipment, retail and service delivery underpins hospitals and schools.�

Darren De Bortoli, Managing Director, De Bortoli Wines

International technology manufacturer Flavourtech (based in Griffith) is supporting the wine industry in the Riverina, and further afield � diversifying into developing technology for the agriculture, beverage and pharmaceutical industries.

�They employ a professional workforce that live in and contribute money to rural economies,� Darren says. �If you don�t have these other sectors surviving, then workforces go elsewhere, there�s less children in the schools, and less teachers are employed. It�s a circular effect.�

And at times like this, when pandemics affect hospitality and tourism businesses such as cellar door wineries, those other businesses can and do offer employment.

If you enjoyed this feature, you might like our story on careers in agriculture.