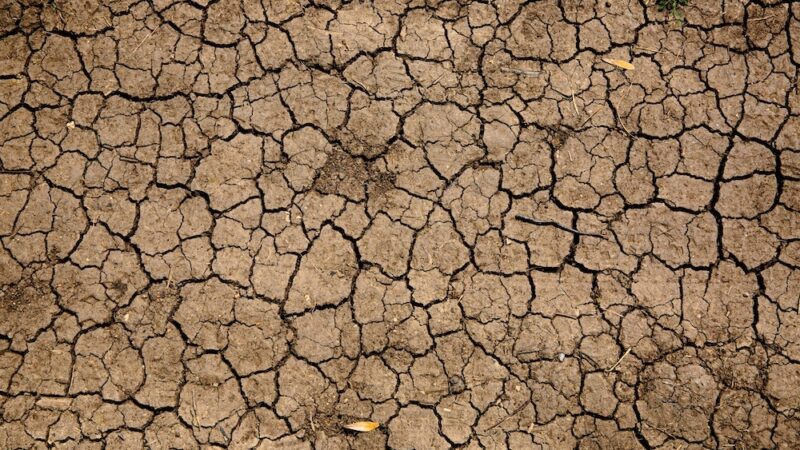

Every year wild dogs destroy millions of dollars worth of livestock across NSW.

The wild dog debate continues

Whether it�s wild dog exclusion fencing, baiting, trapping, or the definition of what a wild dog is, discussion about each of these topics is dynamic.

According to Australian Wool Innovation, NSW farmers produce about 39 per cent of Australia�s sheep flock, and the Merino is 60 per cent of the national breed total. This means NSW farmers have a significant vested interest in controlling any predators that affect their flocks.

The predators with the most effect on sheep numbers in NSW are wild dogs and pigs.

Dogs have been tracked ranging over a distance of 26,000 hectares and crossing state lines. One of the other major issues facing wild dog management plans has been when states implement actions that are in conflict with other states, in a similar way to public land managers� actions, or lack of action, can be in conflict with private landowners.

Given the large range of some wild dogs, control efforts need to ignore land tenure boundaries if agriculture production is going to be protected.

While farmers, industry groups and government employees believe localised engagement in decisions and actions is the best solution for predator management, there are other interested people � sometimes in urban centres � who also want to be part of the decision-making process.

Wild dog versus the dingo

Let�s address early what some people feel is the most controversial topic in this space. What is a wild dog and what is a dingo?

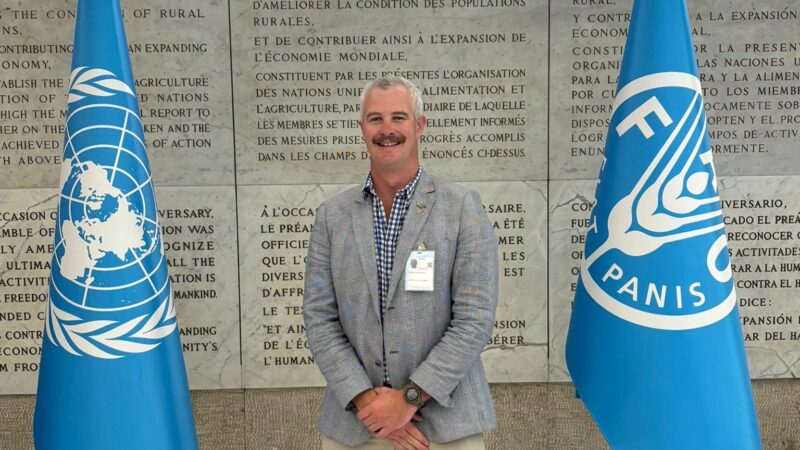

Dr Guy Ballard is a scientist with the University of New England, with significant experience in pest predators, including wild dogs. As a field ecologist he is also Research Leader, Predator Management in the Invertebrate Pest Research Unit within NSW�s Department of Primary Industries.

In Guy�s view, most wild dogs in NSW have a significant degree of dingo DNA � or put another way, many of the dingoes in NSW have some degree of dog DNA.

�In NSW, all dingoes are wild dogs, and not all wild dogs are dingoes,� Guy says.

�The conflict in wild dog management is the perception by some people that dingoes are not wild dogs. People set different levels of priority for what constitutes a dingo. Some people set the bar low, at 50 per cent or below. Some people set the bar high, at 90 per cent or above.�

�There�s no agreed level at the moment. Dogs that are mostly or all dingo keep turning up and that keeps feeding disagreement between people with firm views who don�t agree with each other. In southeast Australia, most wild-living dogs have some dingo ancestry and some modern dog ancestry.�

Dr Guy Ballard, a scientist with the University of New England

Wild-living dogs are those who aren�t living in a domesticated arrangement, either as pet, companion or working dogs. For the sake of this article, we�ll refer consistently to wild-living dogs as wild dogs.

Endemic status of wild dogs

Endemic status of a pest animal, plant or disease means it is consistently present and has become a pest needing localised engagement and management. Endemic status is applied when the pest or disease affects a particular group of people. In the case of wild dogs, that group is largely rural landowners and land managers.

Epidemic, in contrast, is a pest that impacts a broad national population. It could be argued that wild dogs have a broader epidemic impact � particularly from a predation and disease perspective. Wild dogs kill and maim animals and negatively affect a farm�s production system, therefore potentially impacting on food security. The wool and sheep industry across most Australian states and territories is negatively affected by wild dog predation.

However, wild dogs aren�t discriminative. Wild dogs predate native animals. Guy�s team regularly investigate the stomach contents of wild dogs, finding the remains of bandicoots, kangaroo, deer, wallabies, koalas as well as sheep, goats and cattle.

�People are quite sympathetic towards sheep losses but ignore cattle losses and there�s not a clear linkage in the public mind about wild dogs predating on native wildlife, including threatened species.�

Dr Guy Ballard � a scientist with the University of New England.

There�s also disease risk brought by wild dog predation. The species carries and spreads hydatid and neospora caninum which affects other mammals. Mauling activity on farmed and native animals requires antibiotic and crush injury treatment, or euthanasia. Antibiotic use restricts market access for farmed animals. Crush injuries also affects the production value of farmed animals.

�There needs to be a continuing high priority and funding allocation to pest management,� Guy says. �If I had another 20 staff on my team, they�d all be busy.�

Technology supports control and response initiatives

Technology is making a difference in understanding wild dog behaviour and how predators should be managed. Integrated control programs of baiting, trapping and shooting are making a difference, according to some of the farmers involved.

As many wool growers are aware, Australian Wool Innovation (AWI) has been involved for many years with financially supporting wild dog trapping and baiting programs, involving more than 170 regional groups.

AWI still oversees daily operations of the National Wild Dog Action Plan, and relies on other industry partners and local farmer groups for implementation of actions. Local Land Services employs a network of biosecurity officers across NSW to help coordinate group control programs.

In all the regional strategic pest animal management plans in each of the 11 LLS regions, wild dogs are listed as a priority species. In the Western LLS, the Professional Wild Dog Controller program engages 85 properties and the cost of employing controllers is shared between LLS and private landowners.

Since February 2020, six controllers in the Western LLS have eliminated 125 wild dogs. In the Upper Hunter region, more than 70 dogs were removed last year, utilising 1,040 traps across the landscape and night-vision cameras to track dogs. LLS and many farmers are using cameras on public and private land respectively, to identify and track movements and activities of wild dogs.

Farmers have also been involved in the Western Tracks project, catching wild dogs and fitting them with GPS collars before releasing them. The Western Tracks project is part of a coordinated localised response that includes aerial and ground baiting that began in 2014 and a trapping program which began with local farmers and was taken up by LLS.

The movements of the collared animals are revealing important information, according to NSW Farmers� member Leon Zanker, who is chair of the Western Tracks Advisory Board, a group of landholders researchers and government agencies overseeing the project.

�Trapping was the circuit breaker. But our constant question was, where are the dogs coming from and what are they doing?

�Most landowners weren�t overly keen to trap, collar and let go a wild dog. Knowing the research project would would assist in answering that question.

�One dog�s home range was 60km long by 20km wide. We identified with the GPS collar and cameras that it crossed our bait lines many times before it took a bait one day. If there�s enough baits out there, dogs will succumb eventually and take one,� he says.

Leon said although sometimes it didn�t feel like it, coordinated baiting and trapping and engaging all landowners and land managers in a region had made a difference.

�We have to remain vigilant to where dogs are and what they�re doing and react straight away to a sighting or predating,� he says. �If we become blas�, the dog numbers will build up quickly.�

His view is supported by John Rolfe, a NSW Farmers member on the Braidwood-South Coast Wild Dog Management Plan group. The group enables farmers and public land managers to �thrash out what�s needed,� John says.

�Wild dogs have been a problem for 35 years and their predating takes a physical, mental and emotional toll, as well as severe impacts on production and livestock health.�

He has laid out baits, employed controllers and erected his own safety fencing, along with lights, to protect his sheep overnight from wild dogs.

�In that paddock the dogs wouldn�t touch the sheep. After three months of locking them up at night, I relaxed, and a wild dog predated the flock. You can�t leave your livestock alone,� he says.

John is a strong advocate for coordinated control programs, particularly ground and aerial baiting in large tracts of inaccessible country by public land managers that supports what farmers are doing on their own properties.

He drives along a 29 kilometre trap line every morning and lets his local wild dog controller know where traps have been sprung.

Competing priorities

NSW Farmers has estimated the management of wild dogs by individual farmers and public land managers costs $50 million annually, while feral pig incursions costs the Australian agricultural industry more than $100 million a year.

Across NSW, the organisation�s members are reporting increasing numbers of wild dogs, pigs and feral deer. CSIRO recently reported feral cats were responsible for 1.8 billion native animal deaths each year.

Within Australia�s region, an outbreak of Foot and Mouth Disease in Indonesia has caused alarm, while FMD is endemic in India, and Lumpy Skin Disease is spreading on the Asian continent � all disease management issues of concern to Australia�s biosecurity. In August, NSW Department of Primary Industries detected Varroa mite on nine properties across the Hunter region.

These are just a few of the hundreds of pests and diseases competing with wild dog predation for funding allocation in the private and public space.

NSW Farmers Western Division Council chair, Gerard Glover, said people in general needed to be concerned about the vast numbers of feral cats in the landscape, but pigs and wild dogs remained the main concern for farmers.

�Cats and foxes typically prey on small native animals, which is a big concern. Wild dogs and pigs are attacking livestock. You need good, coordinated controls that everyone sticks to, otherwise you get these population explosions,� Gerard says.

Neil Baker, a farmer in the Tweed region, said all private and public landowners needed to be a part of coordinated pest control programs.

�The rules around controlling pest animals are clear, and everyone needs to be held to the same standard,� he says.

The National Wild Dog Action Plan Coordination Committee met in Canberra in June this year to review progress and set the next strategic direction for raising awareness of the impact of wild dogs and coordinating the tools available to manage and control their predation. The plan�s focus going forward included multi-species predator management and impacts on agriculture more broadly.

Documenting wild dog activity

Since 2016, hundreds of people have used FeralScan WildDogScan to document wild dog activity across NSW. It is now a mobile phone app, in a program managed by the Centre for Invasive Species Solutions, funded by the Federal government and AWI grower levies. The online application enables farmers and land managers to upload GPS coordinates where they have seen signs or identified wild dogs.

Fortunately for rural people using Australia�s unreliable mobile phone service, WildDogScan does not rely on mobile connection to upload information. The localised information � photos from fixed cameras, dead or mauled livestock, and sightings of live dogs, scats and disturbed baits or traps � is shared with neighbouring farmers, local dog controllers and the LLS. Across Australia, there are 215 landholder groups using WildDogScan, and 149,740 reports of wild dogs, including 24,015 recent reports.

Fencing for protection against wild dogs

Every state on Australia�s mainland has a plan for fencing against wild dogs. Cluster and exclusion fencing is chosen depending on private landowner and government preference and travels across steep country, waterways, sand and some isolated terrain. Some of the fences are electrified, using solar power, and standoffs can be incorporated into fences.

�The type of fencing built is dictated by regional preferences,� AWI�s Ian Evans says. �You�re better off to teach pest animals not to approach fences, by using electrified fencing, including stand-off wires. Cluster fencing has changed the situation where it�s installed, providing a barrier for anything from three to 33 properties.

�I think fencing is very important and long term that�s how we can make a difference, alongside baiting and shooting. The fencing creates dog-free areas. Building, repairing and monitoring fences in Australia will be an endless process.�

Mr Evans said installing motion controlled cameras identified proof of the effectiveness of electric fences against wild dogs.

In the rangeland Paroo district, professional trapping programs had a big impact on reducing wild dog populations. Farmers participated in training to set traps, to support the professional controller, and coordinated baiting programs. Then local farmers decided to participate and invest in a cluster fence initiative, to exclude wild dogs that were travelling from other regions. It has now given local farmers a more assured future in agriculture.

If you enjoyed this feature on wild dogs, you might want to read our story on the wild dog fence saving quolls.