The United Nations declared 2012 the International Year of Co-operatives and Australia marked it as…

On the frontline of biosecurity

We need better biosecurity at the border,� says NSW Farmers president James Jackson.

�We need a levy that helps pay for the cost of checking overseas tourists, as well as their packages and containers. It�s the responsibility of importers to pay for the cost of biosecurity.

�The people who benefit from the trade of importing goods, should pay for the risk. We don�t want to rely on the lucky chance of an entomologist opening the door of his new imported fridge and a beetle dropping out.�

NSW Farmers president James Jackson.

There are a number of issues related to biosecurity, including inspections of products and containers, how traceability reinforces producers� responsibilities to global markets, and integrated risk. Farmers, industry bodies and the NSW Government are key partners in protecting the State from disease and vector incursions. Australia�s geographical isolation has meant that our farmers have to deal with few of the pests and diseases that affect agriculture industries overseas. The efforts of everyone else is undermined if the Commonwealth government is not protecting food and fibre industries and the environment from pest and disease incursions.

Last year, the Commonwealth Government failed to adopt the Onshore Biosecurity Levy (also known as the Biosecurity Imports Levy), and stated there would be no replacement program. The Government cited COVID-19 among its reasons for ceasing the program and lack of replacement action, even though a report requested by then Minister for Agriculture, Senator Bridget McKenzie, and received in 2019, recommended increased funding and improved data control and management.

The authors of the report, Biosecurity Imports Levy: A Way Forward (May 2019, updated September 2019), cited concerns about the varying level of taxpayer funding provided year-on-year to prioritise biosecurity and the lack of data available to quantify and validate funding. They noted biosecurity was becoming increasingly complex and needed to be at least part-funded by importers.

�Biosecurity needs to be better funded at the national border level. Once a bug gets into the country, it�s a State and Territory responsibility. When the state decides they can�t deal with it, they call it endemic and it becomes the farmer�s responsibility.�

NSW Farmers president James Jackson.

NSW�s Department of Primary Industries, for instance, is trying to identify why containers of whitegoods and children�s highchairs were not fumigated or checked for khapra beetle by Commonwealth Government agencies.

Other biosecurity risks that arose in 2020 include fall army worms, leaf miners, influenza and stink bugs. Here we delve further into the main issues.

Khapra beetles

The khapra beetle is a destructive pest and a significant biosecurity risk to Australia�s grain industry. The beetle is found in at least 75 countries throughout Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Movement vectors include items such as imported grain, foodstuffs, machinery, cargo, mail and travellers.

This century, the khapra beetle has been found in shipping containers on at least three occasions in Australia � in Western Australia, South Australia and New South Wales. This year�s discoveries have been in WA and NSW.

If the beetle was to establish itself here, many of Australia�s trading partners would reject our stored produce, and 80 per cent of Australia�s grain exports would be at risk if it was classed as endemic. As Australia exports much of the grain we grow, the beetle could cause huge losses, affecting Australia�s economy.

�Like most biosecurity incursions, the risk to agriculture is attached to everyone, including tourists,� James says.

Fall army worms

Since 2016, fall army worm (FAW) has spread throughout Africa, the Indian subcontinent, China and southeast Asia. There are approximately 350 plant species hosts, including economically important cultivated grasses such as maize, rice, sorghum, sugar cane and wheat; also vegetable and fruit crops and cotton. FAW was detected in NSW in October.

FAW eggs hatch within two to four days after being laid on lower leaf surfaces. Adult FAW moths are strong flyers and will travel hundreds of kilometres on storm fronts. The larvae can also be spread in cut flower, fruit and vegetable consignments.

Fortunately, the same parasitic wasp can be used against FAW and cotton bollworm, as part of integrated pest management (IPM). Parasitic wasps have proven effective with up to 70 per cent control of FAW, by laying their eggs on or inside FAW eggs and larvae.

The cotton bollworm, or corn earworm, is widely distributed across Australia, particularly in the eastern states. The bollworm evolves rapidly against insecticides; but since the mid-1990s, Australia�s cotton breeders have been including Bt insect resistant genes in seed varieties.

CSIRO research reinforces industry data that there has been an 80 per cent reduction in the use of chemical pesticides previously required to control bollworms. This means safer working conditions for growers and it is also beneficial for the environment.

Leaf miners

There is one species of leaf miner under management in the Peninsula area of Cape York. From July last year, after serpentine leaf miner was detected on chrysanthemums coming into Australia from Malaysia, importers have been required to apply methyl bromide fumigation. Leaf miners affect many vegetable, legume, fibre (cotton), fruit and flower crops. Importation of infested plants, plant material or soil is the most likely way that leaf miners could make it to Australia.

Influenza

The domestic and export market for chicken meat and eggs was affected by regional and border closures in 2020. Outbreaks of Avian influenza � H7N7, H5N2 and H7N6 strains � were detected among commercial poultry birds in Victoria. After a successful eradication program supported by multiple states and Animal Health Australia, on 26 February 2021 Australia officially regained freedom from highly pathogenic avian influenza in accordance with international guidelines published by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). Known as proof of freedom, this official evidence is an important milestone in re-establishing export markets for Australian poultry and egg farmers.

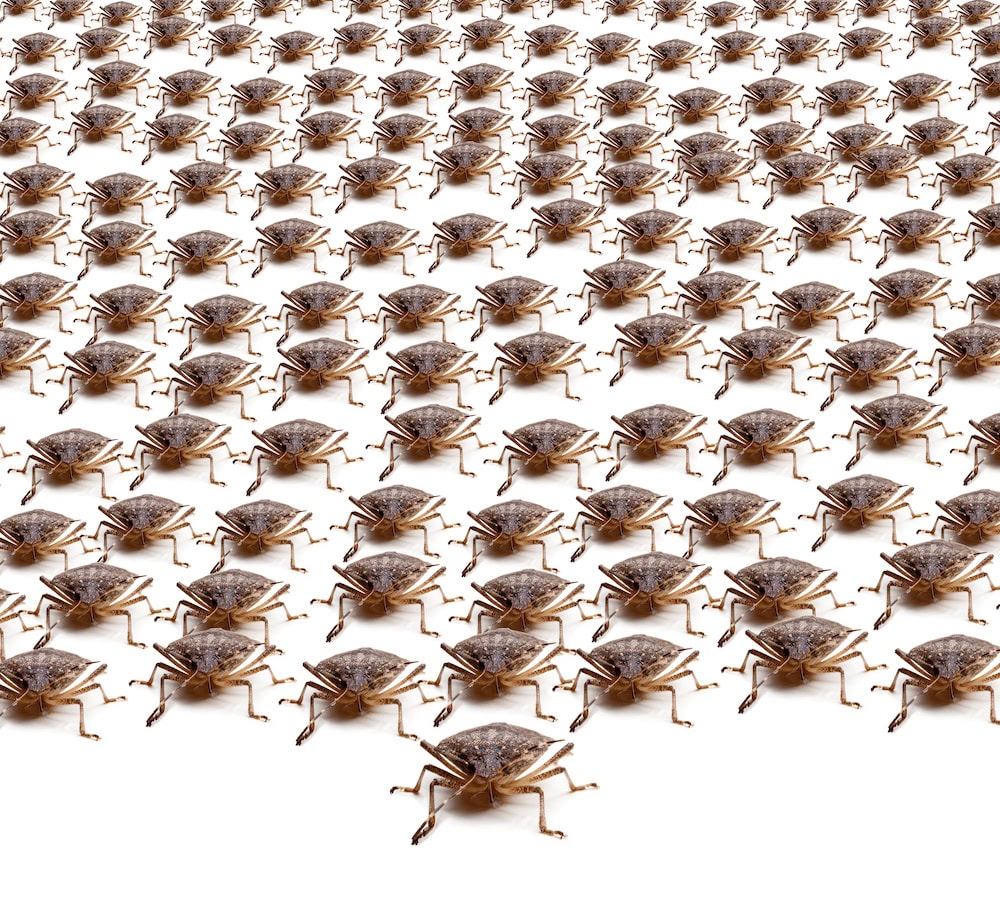

Stink bugs

Ships were stopped from unloading when the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) was detected as a hitchhiker pest on containers in Australian ports early last year. The BMSB feeds on 300 plant species, including agricultural crops such as nuts, grains, berries, cotton, citrus, soybean and some ornamental and weed plant species; it is classified as a significant biosecurity risk for Australia�s agricultural industries and the environment.

African Swine fever and foot and mouth disease

African swine fever (ASF) and foot and mouth disease (FMD) virus fragments were again detected in pork products seized at Australia�s international mail centres in a two-week period over the Christmas holiday period.

These findings do not change Australia�s FMD or ASF-free status, but they do highlight the significant biosecurity risk these products pose for the nation. Minister for Agriculture, Drought and Emergency Management, David Littleproud, said FMD was considered the biggest animal disease threat to Australia�s agriculture.

�An outbreak of FMD in Australia would lead to the closure of major livestock, beef, lamb, dairy and pork export markets with serious economic and social effects in other sectors, including tourism,� Minister Littleproud says. �Studies have estimated a large multi-state outbreak of FMD in Australia could result in economic losses of $50 billion over 10 years and an outbreak of ASF could cost Australia $1.5-$2.3 billion over five years.�

The pork products were seized at international mail centres in Brisbane, Perth and Sydney. Overall, 24 per cent of samples tested positive for ASF virus fragments and 1 per cent tested positive for FMD virus fragments.

Effective traceability

Innovation is improving through-chain traceability for Australia�s farmers. Technology provider Gravotech Australia and NSW Department of Primary Industries are identifying the best laser tattoo method suitable for melons. Success will decrease the amount of plastic used and discarded into the environment, and provide validation in the supply chain that when the customer buys an Australian melon, it is grown in Australia.

On a more local level, Australia�s truck drivers regularly practice traceability requirements to ensure grain and oilseeds are clean of residues that can cross-contaminate food being exported and risk our global markets.

Matters of compliance

The same imposed expectation of compliance needs to be part of the work of Australia�s national border controllers. NSW Farmers wants the Commonwealth Government to move into the modern era, ensuring quarantine officers not only double-check that paperwork submitted by an importer complies with requirements, but using technology to reinforce the nation�s border control.

NSW Minister for Agriculture Adam Marshall recently said the economic cost of biosecurity breaches was increasingly borne by NSW, Victoria and Queensland.

�It�s safe to say we�re terrified about what could potentially happen. Even collectively, the three states do not have the resources to do our work plus the Commonwealth�s job.

�Khapra beetle can enter Australia on plant products as a hitchhiker pest in sea containers. Changes to the management of sea containers to address hitchhiker risk needs to be Australia�s most urgent priority.�

NSW Minister for Agriculture, Adam Marshall.

New systems for the future

James Jackson wants to see blockchain technology integrated into Australia�s national border protection. While the Full Import Declaration (FID), appropriately completed, is an authoritative document, it could be enhanced using new technologies to gather science-based, quantifiable data on biosecurity risks.

This would enable a history of container ships to be part of the data available � block chain technology would identify if a container has been in a country endemic with Khapra beetle. This knowledge would alert Australia�s border inspectors to isolate that shipping container so it can undergo testing.

A system adopting these technologies would also alleviate the risk of holding up ships.

A levy could be applied to the FID to fund biosecurity border control, by slightly modifying the declaration. This recommendation was made to Senator McKenzie in 2019.

�We need an improved tracking and tracing system, and a levy imposed against importers that pays for the cost of checking overseas tourists, packages and containers,� James says.

NSW Farmers has joined with the State Government to pressure the Commonwealth to increase biosecurity and border control funding in this year�s national budget and implement a levy such as the Onshore Biosecurity Levy.

Australia�s geographic isolation has meant there are relatively few of the pests and diseases that affect agriculture industry overseas.

�However, there is a growing risk of exotic disease outbreaks and pest and weed incursions fuelled by the transfer of goods between countries, including bulk, container and parcel post. This is further increased by the movement of people around the world,� James says.

If you enjoyed this feature on biosecurity, you might like our feature on the varroa mite.